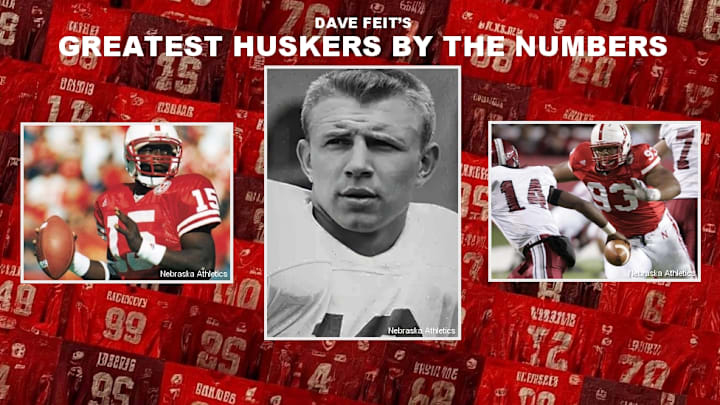

Dave Feit's Greatest Huskers by the Numbers: 12 - Bobby Reynolds

Dave Feit is counting down the days until the start of the 2025 season by naming the best Husker to wear each uniform number, as well as one of his personal favorites at that number.

For more information about the series, click here .

To see more entries, click here .

Greatest Husker to wear 12: Bobby Reynolds, Halfback, 1950-1952 Honorable Mention: Van Brownson, Turner Gill, Dave Humm, Jarvis Redwine Also worn by: Clete Blakeman, Omar Brown, Joe Dailey, Mike Fullman, Joe Ganz, Luke Gifford, Ron Kellog III, Bobby Newcombe, Patrick O'Brien, Courtney Osborne, Chubba Purdy, Tom Sieler, Ernie Sigler, Tom Sorley Dave's Fave: Turner Gill, Quarterback, 1980-1983 Allow me to describe my happy place: It is a crisp, yet sunny autumn afternoon.

Short sleeves now, maybe a sweatshirt when the sun goes down.

A drumline stands at the middle of a football field and starts to play a cadence.

From the heavens (or, perhaps, the speakers behind me) a voice rings out: " It's showtime, as the Cornhusker Marching Band takes the field to begin another pregame spectacular! " Hundreds of band members appear from all four corners of the stadium, marching in single file.

"Now is the time for the Marching Red experience! Presenting the University of Nebraska Cornhusker Marching Band!" The band members continue to rush onto the field, forming single-file lines from goal line to goal line.

Bright red pants, crisp white uniforms with a golden sash, and an 8-inch-tall plume of red feathers on top of their red and white marching band hats.

There must be 300 of them on the field.

"This is the Pride of All Nebraska." The band plays its first notes and the hairs on my arms stand straight up.

The baton twirlers and drum majors are introduced.

Color guards on both goal lines start marching toward midfield, their red and white flags twirling in unison.

"It's football Saturday in Memorial Stadium and there is no place like Nebraska!" A tidal wave of happy memories washes over me.

The amazing games, legendary players and championship teams I've watched.

The nervous anticipation before a big game.

The games I went to with my dad.

The games I've been to with my son and daughters.

Games spent standing next to my best friends.

All of them started with those 13 words.

The band plays "There Is No Place Like Nebraska." Eighty-five thousand people suddenly lose the ability to clap in unison.

Seriously, that moment - and the rest of the "pregame spectacular" (with its salute to fans in all four stadiums) - is one of my favorite parts of a home game.

After "No Place," we welcome our visitors by playing their fight song.

I've been to lots of other college football stadiums, and few (if any) play the other team's fight song.

It's such a quaint, Nebraska-nice tradition (even if the students and fans sometimes boo the other team).

Next comes the national anthem, followed (hopefully) by a flyover of some aircraft.

After the Star-Spangled Banner, we get to the remainder of the band's setlist: The well-known football classic "Mr.

Touchdown, U.S.A." The majestic strains of "March Grandioso" Then let's all chant the letters of Nebraska with "March of the Cornhuskers" And finally, Nebraska's own "Hail Varsity" I love that the Pregame Spectacular has remained essentially the same for nearly 40 years.

Sure, some of the formations have been tweaked, and a couple of songs ("Glory of the Gridiron" and John Philip Sousa's "University of Nebraska March") have been phased out.

But a Nebraska fan from 1987 or 2025 would likely say it's the same show.

But let's focus in on one of those songs: "Mr.

Touchdown, U.S.A." How did that song become a staple of the band's performance? That song is a well-known football classic - it was a top-10 hit when it came out - but I've always assumed it was primarily there as peppy, football-related filler until Nebraska's own "Hail Varsity." It turns out there is a direct connection between that song and the University of Nebraska.

"Mr.

Touchdown, U.S.A." was composed by Ruth Roberts and recorded by Hugo Winterhalter in 1950.

RCA Records - which released the song - staged a promotion where the college football player who scored the most touchdowns in the in 1950 season would receive a RCA television, the title of "Mr.

Touchdown, U.S.A." and a silver-plated copy of the record.

The winner? Bobby Reynolds of Grand Island, Nebraska.

The Cornhusker sophomore sensation scored 22 touchdowns in 1950.

The free TV was delivered to his parents' house in Grand Island, but it did not get used for several years.

At the time, there was no TV reception in Grand Island.

It's hard to adequately describe the impact Bobby Reynolds had in 1950.

He ran for 1,342 yards and 19 rushing touchdowns, school records that would stand until Mike Rozier's Heisman Trophy-winning season 33 years later.

Reynolds was also Nebraska's kicker and punter in 1950.

For the season, he scored a (then) record total of 157 points.* And all of it in just nine games.

*In 1950, the entire Nebraska team scored 267 points, the most by a Nebraska team in nearly three decades.

Bobby Reynolds accounted for 157 of those points, a staggering 58.8% of all points scored.

For comparison, I looked at the rest of Nebraska's Top 10 Points Scored in a Season list.

As you would expect, there are some big names on that list: Mike Rozier, Eric Crouch (twice) , Ahman Green, Ameer Abdullah, Alex Henery (twice), Scott Frost and Kris Brown.

Alex Henery's 2008 season, where he scored 110 of Nebraska's 352 points - 31.3% - is the next-closest percentage of team points scored by a single player.

Everybody else was between 19 and 27%.

In his first career game (against Indiana), Reynolds rushed for a school-record 187 yards, breaking the previous mark by 63 yards.

He scored all 20 of Nebraska's points.

Against Mizzou , "Mr.

Touchdown" earned his nickname with one of the greatest individual plays in school history.

The Huskers were in a shootout with the Tigers.

On 4th & 1 from the Missouri 33, Nebraska opted to go for it, giving the ball to Reynolds on a sweep.

The box score shows it as a 33-yard touchdown run.

But here is how one of the reporters at the game ( Bob Broeg of the St.

Louis Post-Dispatch ) described it: "Reynolds, starting wide on a lateral, was trapped behind the line.

When he saw he was about to be tackled, he swung back in the other direction.

But again, he was trapped, and again he reversed his field, dropping back to his own 40, nearly 30 years behind the line of scrimmage." I'll pause here to note that Nebraska was leading by just six points, and Mizzou had rolled up nearly 450 yards of offense to that point (they finished with more than 500 yards).

In other words, if Reynolds gets tackled at the NU 40, it is likely Nebraska will lose this game.

Back to Mr.

Broeg's recap: "He hand-faked one guy, swivel-hipped another and set out for the goal line now 60 crow-flight yards away.

He picked up three nice blocks, stepped away from another tackler and took advantage of two more blocks.

It was an astounding run.

The kid stands out like a neon light." The 1951 yearbook estimated that Reynolds covered 104 yards on his 33-yard touchdown run.

The only thing that comes close to the run are the stories from his teammates.

Quarterback Fran Nagle: "I gave handed Bobby the ball and he started around the right end.

The next thing I knew, he came running by me again going the other way." Nagle tried - unsuccessfully - to throw a block.

"So, I just sat there on the ground and watched.

Sure enough, pretty soon here came Reynolds running by me for the third time - going to the right again.

"It was a great run to just sit and watch," Nagle told the Lincoln Star .

"But I think some of the guys blocked three or four different people before the play was over." Nebraska tackle Charles Toogood was not one of those players.

According to him, after he pancaked a Missouri defender, he simply laid on top on him.

The Tiger player pleaded, "Let me up! The play's over." Toogood replied, "Not necessarily.

He might come back this way again." In 1950, Bobby Reynolds had to seem like a sunny spring day after the long, grueling winter of nine straight losing seasons.

He earned first-team All-America honors, finished fifth in the Heisman Trophy voting and seemed poised to carry Nebraska back to relevance.

But it was not meant to be.

A long list of injuries kept Bobby Reynolds from recapturing the "Mr.

Touchdown" magic of 1950.

The first occurred at Camp Curtis - Bill Glassford's "Junction Boys"-style boot camp before the 1951 season.

Reynolds separated a shoulder, costing him several games.

In the 1951 Colorado game, Reynolds was tackled after a run.

In those days, lime was used to mark the yard lines on the field.

Some of the caustic material was stirred up and lodged in his eyes.

His left cornea was burned.

The horrible sounding "lime-in-the-eye infection" knocked Reynolds out of action and nearly cost him the use of that eye.

Reynolds scored only two touchdowns in 1951.

As a senior in 1952, he battled an ankle injury and separated the other shoulder in the Kansas State game.

That spring, Reynolds broke a leg sliding into home for the NU baseball team.

That injury ended his chances of playing professionally.

Over his final two seasons, Reynolds had just 854 yards and six touchdowns.

He missed seven games completely due to injury.

Even with two injury-plagued seasons, Bobby Reynolds is still one of the greatest players in Nebraska football history.

He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1984, less than a year before he died.

They always call him Mr.

Touchdown.

They always call him Mr.

Team.

He can run, and kick and throw.

Give him the ball and just look at him go! Hip, hip, hooray for Mr.

Touchdown! He's gonna beat em today! So give a great big cheer for the hero of the year! It's Mr.

Touchdown, U.S.A.! Football is the ultimate team game.

On every snap, 11 players attempt to work in unison to achieve a common goal.

Each man has his own assignment and responsibilities that are often crucial to the success - or failure - of a play.

The old cliche about a chain being only as strong as its weakest link became a cliche for a reason: It's often true.

Smart coaches know how to work around those weak links.

For example, when I played offensive line in high school, there was a reason most of the running plays went to the opposite side of where I was lined up.

Smart coaches also understand that some links are more important than others.

Quarterback, for example.

Previously, we have discussed the shifts in Tom Osborne's offensive philosophy from his time under Devaney , the Humm/Ferragamo passing years , and the power running that finally helped him beat Oklahoma in 1978.

At the end of the 1970s, Osborne started to embrace the option .

Osborne liked that the option gave him more flexibility than OU's wishbone attack.

But he needed somebody who could run it effectively.

Jeff Quinn - from Ord, Nebraska - was Osborne's first true option quarterback.

Quinn was a very good player (second-team All-Big Eight in 1980), but Osborne knew there was another level.* *Make no mistake, Osborne's offenses between 1977 and 1980 put up good yards and scored points.

The 1977 team averaged 302.5 rush yards per game (sixth best in the nation) and scored 26.7 points per game.

By 1980, Quinn directed the nation's best rushing attack (a school record 378.3 ypg) and second-best scoring offense (39.9 ppg).

But it still felt like there was another step they could take.

As Osborne once said: "You dont want to become heavily involved in option football if you dont have speed at quarterback." To truly elevate the offense, Osborne needed an upgrade at quarterback.

Enter Lance Van Zandt.

He was Nebraska's defensive coordinator between 1977-1980 and as Texan as the day is long.

Van Zandt recruited the Lone Star state for the Huskers and led Nebraska's recruitment of a highly touted quarterback from Fort Worth: Turner Gill.

Gill was a highly coveted recruit in his class.

Home state Texas wanted him, as did Oklahoma.

But Gill really liked what he saw in Tom Osborne - the man, as well as the football coach.

Gill gave his verbal commitment to Van Zandt and Nebraska, and Osborne hopped on a private jet to secure Gill's signature in person.

But the Sooners had other ideas.

Head coach Barry Switzer and OU's baseball coach* camped out at Gill's house hoping for a last-minute flip.

But Gill wasn't home - Van Zandt persuaded him to hide out at a friend's house while they waited for Osborne to arrive.

*An excellent shortstop, Gill was drafted by the Chicago White Sox in the second round of the 1980 MLB draft.

He played for the Nebraska baseball team in 1983, hitting .284.

After retiring from the Canadian Football League, Gill played three years in Cleveland's minor league system.

Gill and Van Zandt picked Osborne up at the airport and headed to the Gill residence so Osborne could visit with Turner's parents.

One small thing...

Nobody thought to tell Osborne that his coaching rival - the man who had beaten him six of the seven times they faced off as head coaches - was sitting in the living room of his prized recruit.

Here's how Gill told it later on: "He looked at me and said, 'Whats going on?'" "I said, 'Everythings fine, Coach.' But you can all imagine Coach Osbornes little stare." Gill played sparingly as a freshman in 1980.

In 1981, Osborne got off to the worst start of his career: 1-2 with losses to Iowa and Penn State.

Gill was third string, behind Mark Mauer and Nate Mason.

At halftime of the fourth game (Auburn), Nebraska was trailing 3-0 and Osborne was ready to take a chance and make a change.

Turner Gill would start the second half.

Gill didn't have good numbers (1-6 passing for 9 yards and an interception, 8 rushes for 20 yards and an 8-yard touchdown), but he led three scoring drives in a 17-3 win.

He would start the following week.

Tom Osborne had the first great quarterback for his option offense.

Keep in mind, were only here to talk about Gills playing career, which is too bad considering Gill coached three of the finest quarterbacks in school history (Tommie Frazier, Scott Frost and Eric Crouch).

Gill was a trusted lieutenant to both Osborne and Frank Solich before taking Buffalo from laughingstock to conference champion.

Of course, Gill is not short of accomplishments as a player.

28-2 as a starter, including three straight Big Eight championships.

Gill never lost a Big Eight game as starting quarterback.

He was the fuse for the Scoring Explosion offense that averaged 52 points and 546.7 yards per game.

The only Husker quarterback to earn first team all-conference honors three straight seasons.

Fourth in the 1983 Heisman Trophy voting, won by his teammate Mike Rozier .

Gill was a superb runner - the first Husker QB to rush for over 1,000 yards in a career - and excellent passer.

After throwing a pick in the 1981 Auburn game, he threw just 10 more over his next 30 games.

When he graduated, Gill was right behind Humm and Jerry Tagge at the top of Nebraska's passing charts.

But more than anything, Gill just had....

It.

An intangible, know-it-when-you-see-it coolness on the football field.

He always looked in complete control of the situation, never rattled.

Sure, it definitely helps when you're surrounded by a Heisman Trophy winner, a future No.

1 overall NFL draft pick, and have Outland Trophy winners and All-Americans blocking for you.

But watch the old tapes and you'll see a quarterback that would excel in today's game.

Nebraska football took a big step forward when Turner Gill stepped onto the field.

The right player, at the right time, in the right position can change everything.

More from Nebraska on SI Stay up to date on all things Huskers by bookmarking Nebraska Cornhuskers On SI , subscribing to HuskerMax on YouTube , and visiting HuskerMax.com daily..

This article has been shared from the original article on si, here is the link to the original article.