[ad_1]

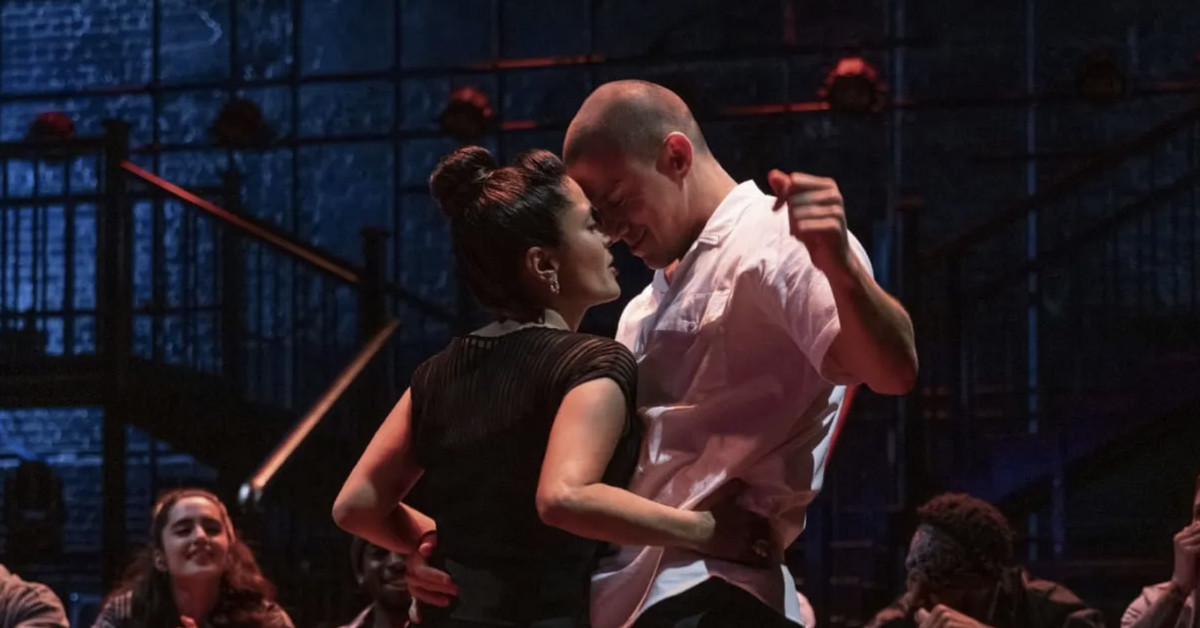

let’s say you want to take yourself magic mike last dance at the AMC 34th Street Theater in Manhattan on Friday. It could happen! Regular tickets are available for $26.88. Or you can pick a seat in the middle of the theater and pay $1 more.

If this was a Knicks game or a Broadway show, this wouldn’t be a big deal. Consumers are familiar with the idea of paying a lot for seats based on desirability and demand. Front-row tickets cost thousands of dollars; nosebleeds seeing foreigners in Las Vegas are more affordable.

But for the beleaguered film industry, this is a new idea. AMC Theaters, the world’s largest cinema chain, announced its ‘Sightline’ plans earlier this week. Most tickets sell at regular prices, but a limited number of seats in the center of the theater cost $1 or $2 more per ticket. The plan will debut this weekend in several locations in New York, Chicago and Kansas City.

It also rubs a lot of people the wrong way. After announcing the program on February 6, AMC CEO Adam Aron defended it on his Twitter two days later, saying the move has extended to a “season of inflation.” That’s probably why I said it.

(2/3) During periods of inflation, prices rise because costs rise. Under the old system, the only option was to raise the price of all seats. Sightline allows us to raise prices only for the most popular seats, but also allows us to keep the rows of standard seats and actually reduce the value of the value seats.

— Adam Aron (@CEOAdam) February 8, 2023

Aron also said that AMC sell the least desirable tickets at discounted prices (more on that later) And — unlike his company’s previous press release, which presented it as an inevitable move that would roll out to all AMC theaters by the end of the year — he sees it as the next I expressed it as ‘Testing’ company ‘closely monitors’”

It’s an uncharacteristically defensive stance for a CEO who’s been operating with mask-like frenzy over the last few years (Aron’s background and his recent turn to memetic stock mastermind are all about this excellent See Businessweek profile). And it shows how deeply rooted the idea of one-size-fits-all ticket sales is in American cinemas. As with the problems inherent in announced price increases, especially when Americans are seeing price increases on everything from energy to eggs.

So while pay-for-seat movie tickets may not stick, they should. They make sense, but there are deep-seated, systemic problems in the theater business. Some are created by their own failures, others by major shifts in how we consume entertainment. If you prefer watching movies in your room with other people instead of on your couch or phone, you’ll have to make a few changes.

“They should have done that years ago,” said Michael Pachter, an analyst at Wedbush Securities. “I’m surprised no one has done it yet.”

Pachter points out that, like Aron, almost every other entertainment venue has variable prices, and many other deals that we can intuitively understand. When you’re on the plane, you could have paid more or less, depending on when the person sitting next to you bought their ticket.

I’m also used to paying different amounts based on when and where I watch movies. You can pay the US average of $11 for a ticket when the movie comes out, or wait a few months and rent it for less. House. Or wait even longer and pay nothing when it shows up as part of a Netflix, Disney+, or HBO Max subscription (nothing really, but it will feel that way).

The movie industry has also regularly attempted to vary prices based on the type of show in the theater. In the late 1990s, Edgar Bronfman, Jr., then-owner of his studio at Universal, suggested that expensive-to-produce films should also cost more for tickets, and was thoroughly panned. However, AMC said he experimented with the idea in 2019 without much fanfare and had very little grief over it.as of last year Batman Upon its debut, AMC raised the price of the film (like other exhibitors) and bragged about it. We expect the same for other potential blockbusters.

Variable pricing also means, as Aron said, that viewers will pay less to see a movie, but studios typically don’t allow theaters to drop prices past a certain level. Still, in theory, AMC’s new seating plan means I could see magic mike AMC has reduced the price of the “value ticket” (in this case, the scratchy-neck front row ticket) by $2, so you get a discount. But to get that discount, you had to join AMC’s fan club, and there was nothing on Fandango’s ticketing app to indicate that the option existed. To be clear, this is an attempt to increase revenue per ticket, not reduce it.

It’s also an attempt to generate more revenue for a deeply troubled business. Either they didn’t like the experience, or because the movie they had watched earlier was being streamed instead. Or scroll through TikTok or YouTube and be happy.

In 2002, Americans went to the movies an average of 5.2 times a year. By 2019, that number had dropped to 3.5 times a year, according to the Motion Picture Association. This trend does not appear to improve after the pandemic. Last year, when the industry celebrated its box office success, Top Gun: Maverickaccording to media investor estimates, the per capita average was still anemic 1.9 Matthew Ball.

This leads to a vicious circle: Low theater audiences have pushed many studios to move more movies to streaming. Stream movies. All of that leads to an empty theater.

As such, AMC is frequently mentioned as a bankruptcy candidate. And why the owner of Regal, his second-largest theater chain in the U.S., filed for bankruptcy last month, closing 39 locations as the industry is still trying to find novel ideas to bring people back to theaters. is. 80 for Bradymovies about older people who like Tom Brady… charge low prices. .

Meanwhile, theaters are cutting costs through fewer staff and online ticket sales, and figuring out ways to raise prices in less obvious ways, such as pushing more expensive food. (although it didn’t save Alamo Drafthouse, a really good chain of boutique theaters, from submitting ).

Ultimately, they will want to increase ticket prices in some way. “The next step is to charge us more.”

That’s probably not what you want to hear. If you still like going to the movies, you should get used to it.

[ad_2]

Source link