[ad_1]

When Julian Katz made his last bet in 2013, the world of gambling was more complicated. To bet on the big games, Katz had to go through a bookie that held his funds in an offshore bank account, circumventing laws banning digital gambling in most countries, including Pennsylvania.

Today, user-friendly instant sports betting apps are everywhere. Katz vowed never to download, but he’s easier said than done.

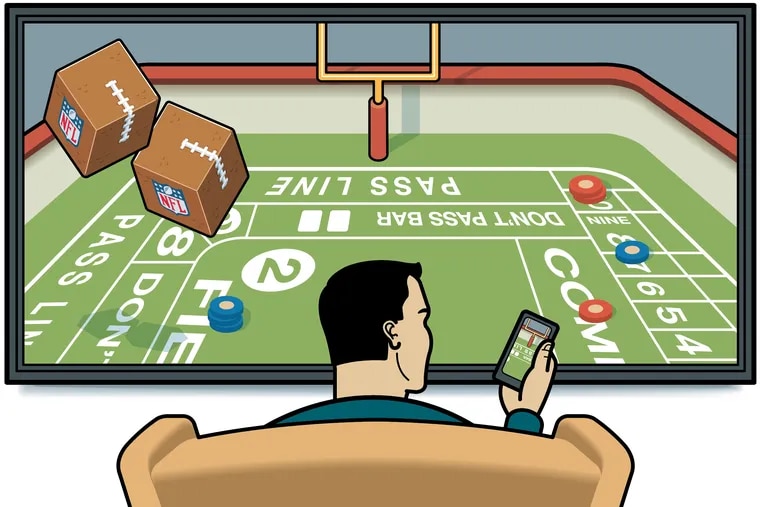

Amid an onslaught of ads from betting apps — dubbed “the casino in your pocket” by gambling recovery experts — Katz says that when watching a Sixers or Eagles game, or most sports, He said he suffers from temptation all the time.

“It’s been really bad for me around the NFL playoffs,” Katz said. “March Madness, really badass. All the advertising and marketing these online his casinos do is thrown in front of us.”

The 36-year-old Philadelphian is hardly alone. Nearly $2 billion in annual national marketing for sports betting apps, stemming from a 2018 U.S. Supreme Court ruling legalizing online gaming and bringing it to Pennsylvania. of people are at risk. Television and Internet advertisements, and even billboards.

With the Eagles aiming for the Super Bowl, the Philadelphia-area recovery program is full of clients struggling to avoid betting apps, according to clinicians. You are overwhelmed with interrupting and constantly popping ads on your phone. Often because of misleading “no sweat bets” that promise to get you back your lost money while encouraging in-app gambling.

“Gambling disorder was recognized as a full-blown addiction in 2013, on the same level as heroin or opioid use,” said a former gambling problem, who founded the Ethical Gambling Reform Group and helped others said Harry Levant, who is providing licensed professional help. people who are having a hard time. “People are going to get hurt when they have nonstop instant access to addictive products.”

The legalization of sports betting has led to an influx of advertising dollars, said Eric Webber, senior counselor at Caron Treatment Centers, which works with problem gamblers based in Pennsylvania.

Nationally, the gaming industry spent about $15.5 million on advertising in 2019, according to Webber.

By 2022, the industry had spent an estimated $1.8 billion on gambling advertising nationwide.

“Anyone with a phone, a laptop, a computer is affected,” says Webber.

Katz, who has built a career as a licensed professional for people with gambling problems, used the skills she learned in therapy to avoid gambling on apps and enrolled in the Pennsylvania Self-Exclusion Gambling Registry. , prohibits you from signing up for the app.

Still, Katz said soccer announcers struggle to talk about spreads and over-unders (common betting outcomes) during intermission.

“Basically, all I have to do is adjust as much as I can,” said Katz. , you have to handle it, accept it, get over it.”

For those like Philadelphia-born Southern Jersey resident John who omitted his last name because of his ostensible sales career, sports betting apps have accelerated a decade-long battle with addiction and made ads harder to ignore. doing.

John began to struggle with gambling in high school, making increasingly large bets at neighborhood bookmakers. He got into a perilous cycle, maxed out his credit cards, took advantage of cash advances, and at one point he lost $40,000 in a month.

A year after John’s first son was born, sports betting was legalized in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. John remembers the day he downloaded his first betting app and was blown away by its ease of use.

Immediately, John was drawn in by the app’s user-friendly interface and seemingly endless betting options. For example, how many rebounds Joel Embiid gets or Doc Rivers calls timeouts. Even more intriguing was that the app was linked to his credit card, allowing him to forget how much money he had bet.

Then John downloaded other stuff and got his attention with flashy promotions.

With a new family to care for, Jon underwent treatment last year after realizing he had to stop his risky behavior. Today he has been over 3 months without a bet. The app is deleted from his phone.

But with John, a die-hard Philadelphia sports fan, rooting for his team, the pressure to gamble remains.

Recently, John watched a Sixers game on TV and the anchor started talking about the odds at halftime. And when he went to see an Eagles game at Lincoln Financial Field with his wife and friends, he was invited to the Fan Duel Lounge. There are no gambling he kiosks in this section, but members are encouraged to wager on their mobile phones.

“It’s not easy,” said John.

Among his colleagues at the recovery center, Webber said the conversation turned to the amount of gambling commercials on television. Even the morning news does. This is not surprising given that major media companies have stakes in the industry.

Walt Disney-owned cable network ESPN struck a big deal with the DraftKings last year to reach a “young sports audience under 35.” Fox Corporation, owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, has launched its own sportsbook, FoxBet, and invests in FanDuel.

The Inquirer has partnered with sports media company Action Network to deliver betting odds directly to the website.

Jennifer Levitt, a certified gambling counselor at the Philadelphia-based Livengrin Foundation, said about three-quarters of her customers had bet on sports or online casinos during the pandemic. The closing of the actual casino coincided with the rapid start-up of the industry.

Levitt was surprised to learn how much Pennsylvania makes from its sports betting tax, but a recent New York Times report on the industry’s advertising activity left her dumbfounded. Caesar’s Sportsbook, which has multimillion-dollar deals with several universities, has placed ads in stadiums, an on-campus mecca frequented by men in their early twenties.

“Once upon a time, you could see tobacco advertisements on television and in magazines and newspapers. “But [betting] Companies don’t want people to stop gambling, so they don’t say it out loud. ”

With gambling companies showing no signs of slowing spending, supporters hope lawmakers can address the industry’s advertising attacks.

In Massachusetts, where Levant is studying for a doctorate at Northeastern University, a Philadelphia-based counselor recently helped draft legislation to include sports gambling as a form of deceptive advertising. .

These promotions lure gamblers to sign up by promising their money back if they lose. There is nothing to do. Instead, you are given in-app credit to continue gambling.

“If a gambler sweats betting in the first place, he has a problem,” Levant said.

Levant said the bill, if passed, would allow gamblers to take legal action against the companies conducting these promotions.

Still, Levant sees federal intervention as one of the most likely ways states like Pennsylvania curb deceptive advertising. State-level restrictions are sparse, aside from a requirement by the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board to include toll-free addiction treatment numbers in advertisements.

Meanwhile, betting ads continue to permeate the daily lives of recovering gamblers.

“Pretty funny, isn’t it?” John said in a message accompanied by screenshots from his phone. day” was written. Above that is an ad for a betting app where you can bet $1,000 without breaking a sweat.

[ad_2]

Source link