[ad_1]

Ⅴernon Vanriel finds it ironic that plays about his life are now considered newsworthy. “For 13 years, no one wanted to know. No one wanted to hear me,” says the former boxer. In fact, Vanriel takes it lightly. For years the British government refused to listen to him. And what a story it is.

The play “On the Ropes” divides his life into 12 rounds. The 11th round was exposed by The Guardian in 2018. Van Riel was a victim of the government’s “hostile environment” policy and the Windrush scandal. Despite having lived in the UK since the age of six, he did not have a UK passport and was unable to return as he spent more than two years in his native country of Jamaica. The 12th is here and now, his life today after returning to his hometown, and his struggle after returning home.

But the other 10 rounds in Vanriel’s life are just as compelling, and perhaps more. And it’s only by hearing the whole story that you can truly understand how Van Riel was first trapped in Jamaica and had the strength to continue it.

Van Riel, now frail, 67 years old, suffers from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure and has bipolar disorder. He lives in North London, close to where he was born and raised, but is not in good enough shape to meet in person, so he speaks by phone. He was with playwright Dougie Blacksland (James Graham-Brown’s pseudonym) and wrote Rope with him. Vanriel’s voice is weak, and he must occasionally gasp to catch his breath. But what immediately shows up is his deep inner strength. This is a man who has survived just about anything life could throw at him and has come out battered but hopeful.

Van Riel today sounds a lot different than he did when he was younger. In the play, he portrays himself as a cocky motormouth, confident to beat any all-comers who enter and exit the ring. He taught me how important it was for me to show not only my good qualities, but also all my flaws. “Dougie told me: I would take this on with you only if you were honest about everything. .”

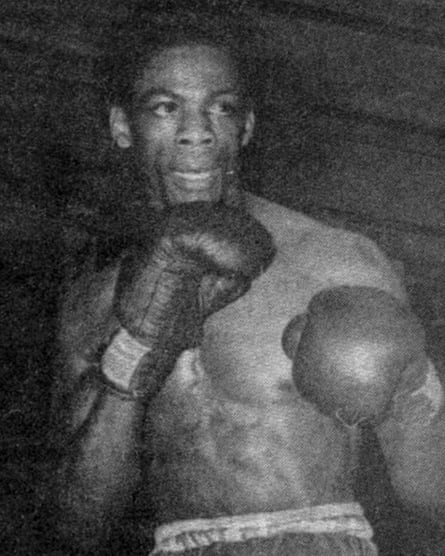

After leaving school, he trained as an electrician and started his own business. By night, he trained as a boxer and worked his way up the lightweight ranks. He turned professional at the age of 21 and was managed by Terry Lawless, who was also Frank Bruno’s manager. With speed and grace, Vanriel danced his way to victory after victory. Fans called him the entertainer, Tottenham his Tornado. He fought in London’s Royal He Albert in front of thousands in his hall and was compared to the great Sugar He Ray He Robinson. He entered the ring in sombreros and flashy outfits, made himself big with poetry like his hero Muhammad Ali, and was a showman at every inch. I would buy a car with a Ford Capri Flash, I was, and that was also the aspect that bothered me.I couldn’t keep my mouth shut.”

Today, Vanriel prefers to be called by his middle name, Josh. Does he think Josh and Vernon are different people? “Dougie and I talked about it a lot. I think maybe this is part of my madness!” he laughs. “The guy who walks the ring is an extroverted show-off, a big gob. Then I’m locked in my apartment, quiet, and sometimes lost.”

As he made his way to the top, it was Gob that got him into trouble. In 1982, he said in a Boxing News interview about how the sport is exploitative: And our boys in the ring were working class, some were white, some were black, but we were all working class, so it wasn’t all racism, it was class. That’s how it was.”

On top of that, he called the promoter a corrupt cartel. “Some promoters said they were only there for the money and didn’t care about us. Looking back, I thought I was the man to speak up. I thought you were bigger than me.

At that time, Lawless told him he could look for a new manager, but would never find one. Guaranteed to give number one George Feeney a crack, Lawless replied that he could stick management where the sun didn’t hit.

Vanriel defeated his next opponent, but never fought Feeney. Outlaws kept the word around. Van Riel was a damaged item. Do you wish he had passed out now? You have to, I say. “All the way. To challenge for that title and become British champion would have been something.”

Vanriel was a disciplined boxer. However, he fell into despair when he lost his chance to fight for the championship. He became addicted to crack. His relationship with the mother of his two British children fell apart and he was split on his second occasion. On one occasion he was severely beaten by a police officer.

“So many boxers have the same fight,” he says. “When it’s all over, the party’s over, and everyone’s gone home, what are you going to do? How do you keep the adrenaline pumping? How do you keep the blood circulating? I’m going the wrong way.” Did he think his addiction killed him?

At that time a recent girlfriend got in touch and told him that he had given birth to his child and invited him to stay with them in Jamaica. I was. Vanriel had a brief period of success as a coach, training young boxers for the finals of the Jamaican Championships. But then his relationship with his new family fell apart and his poor health affected his job prospects. When Vanriel tried to return to England, he found he could not.

He did not know that staying outside the UK for more than two years in a row would mean losing leave to stay indefinitely. He was now virtually stateless. Although he had a Jamaican passport, he was not entitled to benefits or medical care there.

Van Riel finds himself homeless in Jamaica and living in a disused church. One night he made a fire to warm his body. The fire got out of control and the police arrived. That’s when he discovered how worthless his life had become. “One of the officers put a gun to my head. The gun was still pointed at his head, but the officer received a call ordering him to attend to the urgent case. I’m sure I would have been killed if I hadn’t been summoned.

He was charged with arson in the church fire. Now he was sure he would spend the rest of his days in jail in Jamaica. However, after spending more than six months in prison, he was released and returned to life on the streets.

Meanwhile, his sisters in London were fighting for his return to the UK, and his Member of Parliament, David Lammy, got involved. From 1948 (when the Empire Windrush ship brought one of the first groups of West Indies immigrants to Britain) to 1973 (people arriving in Britain from Commonwealth countries were automatically A large number of families arriving from the Caribbean during the cut-off point for being allowed into the country (permanent residency) were being targeted by the government. Some, like Van Riel, were denied permission to return to England. Others were either threatened with deportation or actually deported.

An emaciated Van Riel lived in an abandoned roadside grocery store in western Jamaica. “If by any chance I end up in hell, my experience here has prepared me well. I’ve deteriorated into something unrecognizable,” he told the gentleman. Shortly after she wrote about him, The government relented and he was sent a first class ticket to return to Britain.

Amazingly, his troubles were not yet resolved. Vanriel finds himself in a catch-22 situation. The government has introduced a new requirement that he must have been in the UK five years before applying for citizenship. This was impossible for Vanriel, who was illegally barred from the UK. Despite being airlifted at great expense, he was denied residency.

In 2021, he and Eunice Tumi (another member of the Windrush generation who was denied citizenship under the five-year rule) took the government to court. The High Court ruled that their human rights were violated when the Ministry of Interior refused to grant them citizenship.

“Winning the 2021 trial was huge! It was justice for everyone who lives here, goes to school here, pays taxes here and was told they weren’t British citizens. can’t suddenly rewrite the rules when it’s convenient. conduct that. So it’s a proud moment. That said, justice continues to be denied to victims of the Windrush scandal. Earlier this month, the Guardian revealed that Interior Secretary Suella Braverman was backing out of key promises made in the wake of the scandal.

On the Ropes takes you from the early days of Vanriel to the present day. It’s a beautifully written play, with a Greek-inspired chorus that echoes the voices in his head, and a great score of reggae classics.

What was the experience like writing it? “It was tough and tough at times. I’ve been to some dark places along the way,” Van Riel modestly says. “But it keeps me sane and balanced.”

One of the best things to come out of this play is his friendship with Blaxland. “He’s my Mucker,” says Braxland. “I talk to him every day, sometimes he talks two or three times a day. I learned a lot from him.” Like that? “The lack of humility and self-pity. The little things that haunt you every day seem so small compared to what Josh has dealt with. He’s an amazing human being.”

What does Blaxland want audiences to get out of theater? , there are basic things that should be at the heart of all administration.”

Vanriel let out a breath. “It’s not just from the government,” he says. “from everyone. Everyone. across the board. Compassion, care for each other, and respect. ”

When I ask Van Riel how he survived 11 years of homelessness in Jamaica, he returns to the topic of boxing. “You’ve got to have something to get into that ring in the first place, and you have to stand there and stick. I picture it taking its toll – bipolar disorder, drug addiction, expelled from boxing for his principles, exiled from his own country for his government’s prejudices, imprisoned, beaten. , was almost shot.

And here he is still standing, speaking with such dignity and generosity. Is he really bitter? “I’m too tired to be angry,” he says. “There is a lot of hate in the world. I want them to admit that what they’re doing is wrong, but I don’t want to hate them.

-

Do you have any comments on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a letter of up to 300 words for consideration for publication, please email it to [email protected].

[ad_2]

Source link