[ad_1]

Part I: The Reality Check

IF becoming a boxer requires a degree of dreaming, denial and delusion, it’s fair to say becoming a referee requires quite the opposite. For them, the referee, rather than embracing the fantasy of reaching the top and ignoring the possibility of pain and disappointment, they must instead confront reality early on and understand that any “success” in this profession will not be success in the traditional sense. Forget rewards. Forget fame. Forget success. You are, as the third man in the ring, never thanked, much less celebrated. You are also, if a successful referee, mostly ignored.

This was a reality made clear to the nine candidates who shuffled, somewhat coyly, into a conference room at the Leonardo Royal on a chilly December morning in central London. It was a point made initially by Dennis Gilmartin, the Southern Area Secretary, and one repeated with emphasis by both Robert Smith, the General Secretary of the British Boxing Board of Control, and Richard Barber, the referees’ representative from the Southern Area Council. In agreement, the plan was for each of them to give it to these nine potential candidates straight, with the ultimate aim, that morning and later that afternoon (when another seven candidates entered the same room), of then reducing the number of names on the sheet in front of Gilmartin. It was the first time this process had happened in seven and a half years. In that time, Chas Coakley, Lee Every and Mark Bates, all of whom went through the process, have become A Class referees.

“I’m a big believer in sticking all the doom and gloom in and then if they want to go away, so be it,” said Robert Smith, after which Gilmartin added: “Today’s not about finding a referee. Today’s about getting rid of numbers. We started with 42 and we have had to whittle them down. At this stage we’re basically looking for any alarm bells and red flags. That’s it.”

Thursday, the day Boxing News was granted exclusive access, was the very first step. Once it was over, each of the candidates interviewed would receive a letter notifying them whether or not they had been successful, at which point the successful ones would progress to the second part of the process and the unsuccessful ones would either lick their wounds or perhaps be encouraged to take up a role as a Board inspector.

“The next stage is when we ask a group of you to come to us in a gym environment,” explained Gilmartin, speaking to the candidates directly. “You will on that day have to take part in a test which will be much more rigorous about the rules and regulations the referees with the British Boxing Board of Control are governed by. You will be asked to do at least three example trials in a ring with two licenced boxers. At that point you will also be meeting a Star Class referee who will talk you through their process and how they reached the pinnacle. Not every referee will become a Star Class, for sure, but you will spend time with them. Again, not everyone who goes to that will make it.

“Those of you who are successful will become trainee referees. Being a trainee referee means going to the shows, having a position at ringside, and scoring the fight unofficially from outside the ring. You will do that for quite some time – it could be a year or so. We compare your scores with the scores of the referee officiating the fight, so if you’re miles apart, that’s going to be a bit of a problem. It will also show us that you are turning up for shows, working unsociable hours, and aware you are working on a Saturday night in the middle of nowhere and not getting paid for it.

“At the point the Council feels you are ready to be upgraded, the next step is a triallist referee. That is the first point where you actually get inside the ring with two licenced boxers to officiate a fight that will be on their records. The only difference is you won’t be scoring the contest. A licenced referee outside the ring will be scoring the contest. You, however, are the one responsible for stopping the contest if it comes to that. You have complete control over the fight.

“That triallist part of the process could take another year or so. Again, with you not being paid. Again, with you not being a licenced referee.”

As if to console them, or soften the blow, the applicants were then informed that the Southern Area, the area in which they would – if successful – be assigned, is one of the most active in the country; meaning, the opportunity for them to work on shows and rack up experience would be great.

“This year we have done 307 shows,” said Smith, “which is the most we have ever done. Before that, before the pandemic, it was 250-something. During the pandemic it was 100-something. The biggest area is the Southern, as well as Central and Midlands. But they are both quite far behind the Southern Area.”

If keen enough, scorecards will follow, and so too will the next part of the process: becoming a B Class referee. “At that point,” continued Gilmartin, “you would be a professional referee with the British Boxing Board of Control and you would receive a fee for the shows that you work. At that point you can officiate up to eight rounds. You are the sole arbiter of the contest. You are scoring it and you are refereeing it. I will start appointing you to shows in the Southern Area and it will be your complete responsibility for that contest. That part of the process can take many years.

“If you are successful at that stage, you get recommended to go up to an A Class referee, which means you can referee 12-round fights for no title or certain championships: Southern Area, English, British, a sanctioning body’s regional title. That steps up your responsibility again.

“The pinnacle, which very few people reach, is to become an A-Star Class referee. At that point you can referee a world title fight. You can also referee abroad. You can make a decision who you want to be affiliated to in terms of sanctioning body: WBC, WBA, IBF, WBO, EBU. But that is a long, long way off for anyone. That’s not me trying to put you off. That’s the reality of it.”

The “reality of it” was stressed at numerous points that morning and never once sugar-coated, not even for the purpose of putting nine nervous candidates at ease. If anything, it was instead brought up and emphasised for effect, with the following truths made clear: You referee for the love of the sport, not for money; you are not employed by the Board but merely appointed to work shows by them; it is a thankless task; nobody will know your name and, if they do, you have likely erred; you will inevitably face criticism, however fair or unfair; it is a long, long journey.

“If anyone thought, I’ll apply to become a referee on Thursday and by Monday I’ll be licenced and then by next Saturday I’ll be in Vegas or MSG (Madison Square Garden) doing an Anthony Joshua fight, that’s not going to happen,” Gilmartin stressed to those in the room.

“By the time I get there Joshua will be retired,” quipped one of the candidates in response.

“By the time you get there, there might be boxers who have yet to make their pro debut who will have retired,” Gilmartin was then quick to say. “I’m just being real with you. This is not a financial enterprise. It suits people who are self-employed. It suits people who can make their own working hours. It suits people who might be retired, if they’re fortunate enough to do it. But the point at which you receive any sort of fee – and it’s not a huge fee – you will have done several years for no money. Years down the line you will get fairly paid for your services. You will get your expenses. It won’t cost you anything to be a referee. But it is certainly not anything to get into thinking you’re going to be rich or famous. If you ever become famous, it’s probably because you have done something wrong. You don’t ever want to be famous.”

Indeed, thanks to both the growing power of social media and courts of public opinion, there is perhaps no job more easily scrutinised than that of the designated adjudicator of a fist fight.

“At the very minimum there is a potential for you to be criticised by the boxer you scored against or stopped,” said Gilmartin. “Social media is the biggest change we’ve had in terms of refereeing in the last 15 years. It goes without saying, referees can’t be making comments on social media about boxers when they may be appointed to that same boxer in the next month, six months, or even five years. People will go and find something they said five years earlier, even if you just wrote, ‘I think he’s a good boxer.’ Five years ago you had no idea you would meet this boxer in the ring, but all it takes is one call people deem controversial and those old posts of yours will be brought up.

“Your social media conduct, as a result, needs to be beyond reproach. You need to be very wary of things that can be misconstrued and have an impact on your working career. It would be an awful way to have a career cut short or even impacted. It’s a minefield, social media, for any official working in boxing.”

“It’s not just the criticism you get,” added Robert Smith. “It’s the criticism your family gets. You have to take that on board as well. That has affected my life hugely, in terms of my children going to school. It’s hard to believe they are 25 and 23 now but when they were at school they used to get lots of criticism due to my position in the sport. It affects everybody: your children, your wife, your partner, your parents. You have to be prepared for the criticism that could come your way and also their way. Because it will affect them.

“You might make a mistake, an error of judgement, or you might do everything by the book but someone just doesn’t agree with your call. You might then have the commentators disagreeing with your call and presenting this view to those watching at home. Whatever it is, you have got to make a decision – bang! – and then live with the consequences. Because, having been through it, that’s the main thing: how it affects your life. This is my job. I get paid for this. But you won’t get paid for this for a long time. It has to be your calling.”

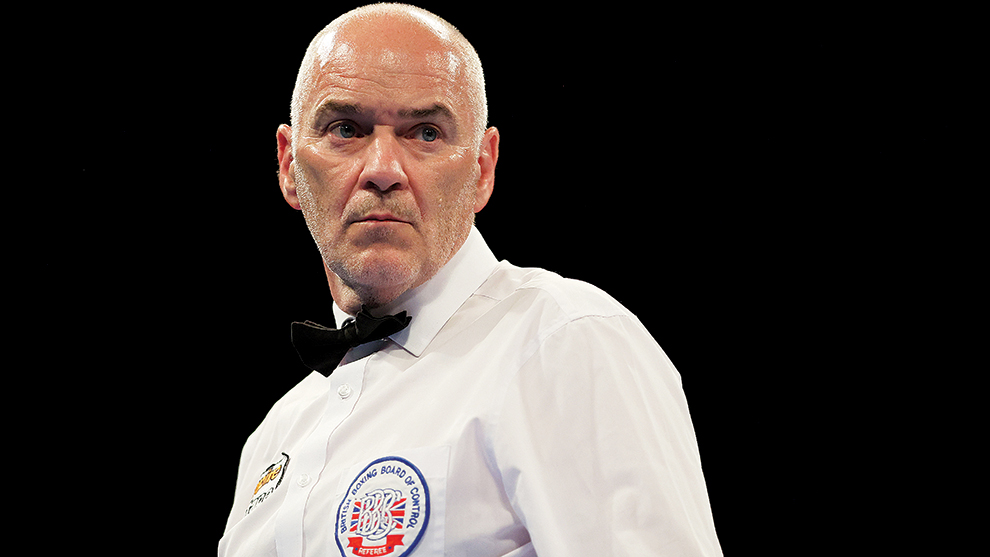

British Boxing Board of Control referee Kieran McCann (James Chance/Getty Images)

Part II: The Interviews

WHEN former professional boxer Rocky Muscus sat at one end of a table and told three members of the British Boxing Board of Control that one of their appointed officials, Ian John-Lewis, had “destroyed” his career, it was not an attempt at retribution, nor, for that matter, as ill-advised as it seems when written down. Instead, by being so honest, Muscus simply revealed both his passion for the sport and an awareness of the consequences of a referee’s actions on fight night. He then proceeded to highlight how, with experience and a greater understanding, he had also come to appreciate the role of a referee more in retirement than he had when competing as a pro.

“He once stopped my fight and it destroyed my career,” Muscus said. “The Board took away my licence and that was the end of it. I ended up on the streets, homeless; no money, no work, no profession. It hit me hard and I hated Ian John-Lewis for years. But then I realised he saw something in my eyes. I didn’t see it.”

Interestingly, Muscus was one of two professional boxers in the latest batch of referee applicants interviewed by the BBBC, with the other current pro Lewis van Poetsch. Now 39, and currently working as a police officer, Muscus started his interview by telling Robert Smith, Dennis Gilmartin and Richard Barber that he had applied for his pro boxing licence 22 years ago, before going on to say: “I believe that people like me need to be in the sport. I was a Board inspector for a few months and I used to see boxers, trainers and referees in the ring and something inside me was telling me that I should be trying to make sure boxers are safe.

“I have dedicated my life to this sport. I know boxers who have had brain damage, like JonJo Finnegan and Howard Eastman’s brother, Gilbert, and I want to be there to be able to be proactive. I want to see something and stop it (disaster) from happening. I know boxing and if I see something and can stop a tragedy happening, I will.”

With 70 amateur bouts and 31 pro fights to his name, Muscus, of all the applicants, was clearly the one most experienced – at least in a competition sense. He was, however, also the one most deeply affected by the sport, not only physically but emotionally and psychologically – for better or for worse. Not just that, there is of course a greater likelihood that former boxers have pre-existing relationships in the sport, which, when attempting to become a referee, could limit them to some extent.

“With your background, do you think there are any relationships that might conflict you if you become a referee?” asked Dennis Gilmartin. “Previous examples have been referees who were maybe trained by a trainer who still trains or referees who have a brother or other relative still active in the sport –”

“We have a referee whose brother is a trainer,” said Robert Smith, referring to Marcus (referee) and Jim McDonnell (trainer). “So that referee cannot referee a contest involving one of his brother’s boxers.”

“Is there anyone you can think of, Rocky, who might conflict you should you become a referee?”

“I was once asked,” Muscus said, “that if I saw my mother or brother doing drugs, would I arrest them? ‘Damn right,’ I said. ‘No favour, and no fear.’ I’ve got a lot of friends in boxing…”

“I get that,” said Gilmartin, “and I’m sure you wouldn’t have a problem making the right decision. But what I’m saying is, is there anything that someone can throw back at you?

Muscus shook his head in a manner both certain and sombre. “Jim Evans has gone. Dean Powell has gone. Jackie Bowers has gone. All the people I knew in boxing are gone.”

Later, when this same question came up again, 28-year-old Toby, who currently works in finance, revealed an association with St. Ives Boxing Academy, for whom he competed between the ages of 16 and 18. It was there, in fact, that he struck up a friendship with the gym’s coach, Steve Whitwell, an old sparring partner of Robert Smith, and also his daughter, Harli, who turned professional in October.

“That’s a perfect example of what we were talking about before,” said Gilmartin. “If you were to become a referee and were appointed to a show six weeks out not knowing who was on the card and then all of a sudden you find yourself appointed to officiate Steve Whitwell’s daughter, it would be one you would excuse yourself from. It’s only to protect you from being criticised.”

Of all the questions posed to the applicants that day, it was one of the more important. Other questions asked tended to pertain to an applicant’s date of birth, occupation, and any known medical conditions. They were also each asked if they had ever been in trouble with the police, as well as questions regarding any officiating qualifications they had in the amateur code.

Surprises, in terms of answers, were few and far between. Indeed, it was only when the day’s first female applicant, Patricia, was interviewed that confusion found its way into the room. “I’m 65,” she said when asked to state her age, not aware of the Board’s strict age limit of 65 for referees. “Oh, I didn’t realise,” she then said when informed of this.

“Would you be interested in another position with the Board?” asked Robert Smith. “Like an inspector.”

“I would be,” said Patricia. “Absolutely.”

Smith soon learned that Patricia’s relationship with boxing began back in 2009 when, shortly after her mother sadly died from a heart attack, she joined a boxing gym through fear of one day suffering the same fate. It was as noble a reason as any to become involved in the sport and her reason for wanting to later become a referee – “I want to be even more involved” – was, as it turned out, not dissimilar to many of the others that day.

“Mr Switzerland”, for example, a global payroll manager so impartial he that morning coined his own nickname, had been inspired to become a referee by the performances of the professional referees he had seen on television. He had, he said, been an avid follower of the sport since watching Ray Leonard and Thomas Hearns do battle in 1981 and had been a subscriber to Boxing News since the age of 13.

“The best stoppage I’ve ever seen was in the fight between Herol Graham and Johnny Melfah (in 1988),” said the now-49-year-old. “That was a perfectly timed stoppage, in my opinion. Johnny was out of his depth and starting to get beaten up and the referee (John Coyle) stepped in very quickly to stop it. I’ve seen others that have gone on too long, of course. Ray Mercer vs. Tommy Morrison (in 1991) went way beyond when it should have been stopped.”

Muscus aside, none of the latest batch of applicants had ever boxed professionally and, moreover, their actual day jobs were impossible to predict; ranging from an HGV driver and life coach to an Amazon delivery worker and mechanical engineer. They were vital, too, these jobs, something Gilmartin stressed from the outset.

“It’s a tough process and it’s good you laboured the point regarding how long it takes,” Robert Smith said to his colleague at one stage. “Dave Parris was a B-grade for 10 years. That’s a long time.”

Speaking of which, Richard Barber, now overseeing things, found himself part of the same process some 25 years ago.

“It was quite intimidating,” he recalled. “There were all these big tables and all the famous referees sitting around them: Sid Nathan, Harry Gibbs. As you came down the stairs into this room you were thinking, Oh, what have I let myself in for? Then they would all fire questions at you.

“Unfortunately, I didn’t know the answers to many of the questions. I got told ‘don’t give up your day job’ and then Robert (Smith) pulled me outside and asked if I would like to be an inspector. I’ve been one ever since.”

“And that was a cockup,” joked Smith. “I’ve regretted it ever since.”

Like their occupations, the ages of candidates tended to also vary. Well below the 65-year cut-off were the likes of 22-year-old David, who worked in hospitality and had just become a C-grade referee and judge, the aforementioned 28-year-old Toby, the 32-year-old Craig, a mechanical engineer who refereed kids’ football matches, and the 34-year-old Bernard, a Ugandan-born Amazon employee who started boxing as an amateur in 2013 in Italy only to move to London two years ago to pursue a career as a professional referee. “I speak Italian, English, and two African languages,” Bernard revealed, which, in terms of skills, sounded every bit as impressive as his C-grade judging qualification with England Boxing. “Oh, and German, too. I forgot.”

Qualifications aren’t everything, of course. Some had them; others didn’t. Some had plenty; others fewer. The HGV driver, for instance, was a B-grade referee and judge and had worked as a Board inspector for the past eight years, whereas the 22-year-old was a C-grade referee and judge with England Boxing but had practised both roles for less than a year. Furthermore, in a mark of his youth, he had finished university during the Covid-19 pandemic, he was currently learning to drive, and he had been introduced to boxing by the 2017 “fight” between Floyd Mayweather and Conor McGregor.

Forty-year-old Amy, meanwhile, a life coach and the group’s second female, is an A-grade referee and judge with England Boxing. She has been competing as an amateur boxer since 2013 and, in addition to that, holds a Level 2 coaching qualification with England Boxing. These achievements, presented to the Board officials that Thursday morning, appeared to not only strengthen Amy’s case but highlighted once again the growing presence of women in both amateur and professional boxing.

“When I was with the Southern Area, which was obviously a long time ago, we never had females applying to be referees,” Robert Smith told me. “But obviously now because the women’s game is getting bigger, they are starting to apply.

“I remember once getting asked by a journalist, ‘Why are there no female referees?’ Well, the reason for that is because women’s boxing has only just got big and therefore it’s going to take at least 10 years to see a female referee in the ring. It’s all a process. You can’t just appoint a referee to a female fight. Once they’re doing the (whole) show, they’re doing the show.”

With nine candidates interviewed and seven still to enter the room, a break was then called. It was during this break the three members of the Board took phone calls, answered emails, or simply ate the sandwiches, chips and fruit on sticks provided for them by the hotel. They also spent much of this break marvelling at the variety of the spread, both in a food sense and, more importantly, in the context of the potential referees with which they had crossed paths that morning. There were, they recalled, both male voices and female voices. There were faces of all colours. There were people from the inside and people from the outside. There was, best of all, an abundance of passion and potential; the only two things that in the end matter.

“Because of our positions, if a referee didn’t turn up at a show, we would have to go and be the referee,” Smith said, gesturing to himself, Gilmartin and Barber. “But the thing is, I’ve never refereed anything in my life other than a kids’ football match. I’ve been a timekeeper when the timekeeper didn’t turn up and I s**t myself. It was a horrible experience.

“Although I’ve been watching boxing all my life, if I was in there refereeing, I wouldn’t know what to do. It’s like scoring a fight. How many times have I sat there thinking a fight could have gone this way or that way and then gone home and watched it back on television and seen a completely different fight?”

In case it was needed, Smith’s words at lunch acted as one more reminder of the fact this role – a role for which so many had applied – is, as well as a thankless one, not for everyone.

[ad_2]

Source link