[ad_1]

Jerry Cotsey, the South African heavyweight boxing champion who has shed the moniker “Great White Hope”, criticized apartheid and earned the respect of Nelson Mandela, will be at his home in Bloubergstrand, outside Cape Town, on January 12. died in he was 67 years old.

The cause was lung cancer, said his longtime manager Thinus Strydom.

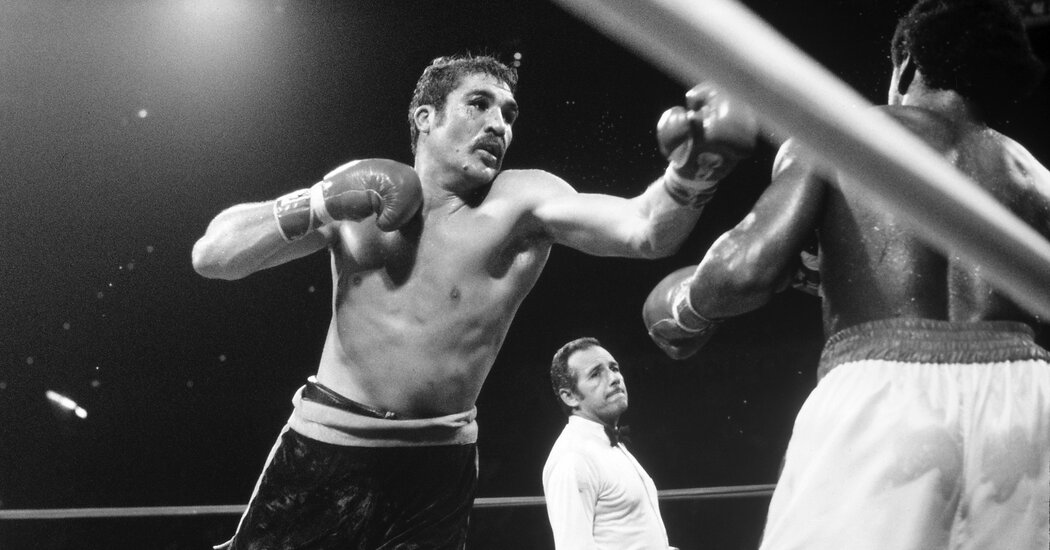

After losing bids for the World Boxing Association title in 1979 and 1980, Coetzee got his revenge in 1983 when he knocked out the previously undefeated Michael Dokes. Gerrie (pronounced helly — rhymes with “Merry” — with a guttural “h”) Coetzee (pronounced coat-SEE-uh) became Africa’s first world heavyweight champion.

At that time, white South Africans could still be described by The Washington Post as “a beleaguered minority” whose attempt at boxing glory represented “a chance for national validation.” did it.

Instead, Coetzee’s fame went against apartheid. His bid for the title in 1979 brought the first racially integrated crowd (81,000) to Loftus his Versfeld his stadium in Pretoria.

Even Tate supporters frequently praised Coutsy when the New York Times asked people in Soweto’s Black Townships for their opinion on the fight between African-American John Tate and the Afrikaners.

“Coetzee is a better fighter, a more principled man,” one schoolboy told The Times.

Coetzee did just that during the pre-match press conference. “What makes me really happy is that black, brown, and white people accept me as a fighter,” he said, adding, “People are treated on merit, not race or color. should,” he added.

International sports competitions generally ban South African athletes, making Coetzee one of the country’s few global athletes. Both whites and blacks in South Africa crowded around the radio in the middle of the night to hear the broadcast of his fight abroad. One of his amateur boxers looking for diversion during his 27-year imprisonment was Nelson Mandela.

According to Strydom, he sent Coetzee a letter of encouragement before the Battle of Doakes, and Coetzee replied by sending him a videotape of the victory. The men faced each other in a boxing stance and smiled.

Coetzee’s independence was not only ideological. In interviews, he refuted his expectations of a professional boxer and spoke softly about the boxers who threatened him. He interrupted his training to work as a technician in his friend’s dental laboratory.

When Coetzee traveled, he called home every day to check on Wendy, the companion he always wanted by his side. Wendy was an English Cocker Spaniel that I bought when she was a puppy.

“I didn’t really like Wendy in bed,” Coetzee’s wife told The Times in 1982. Now she loves Wendy as much as I do. ”

Gerhardus Christian Coetzee was born on April 8, 1955 in Johannesburg. He grew up in the nearby mining town of Boksburg. His father, Philip, was an auto mechanic who ran a local amateur boxing club. His mother, Meisie (Vu Vuurs) Coetzee, was a homemaker.

Jerry was a shy boy and wasn’t particularly interested in boxing, but his father paid him 50 cents a week to spar. By age 13, he won the state bantamweight title.

He turned professional in 1974, boxing while studying to become a dental technician at the University of the Witwatersrand. He graduated in 1976.

He rose to fame in June 1979 when he faced off against Leon Spinks. Leon Spinks said that a year before Mohamed he had his two famous bouts with Ali, winning the first and losing his second, but was temporarily the undisputed heavyweight. won the title of class champion.

In what the announcer called an “amazing upset”, Coetzee crushed Spinks, knocking him down three times in the first round. The decisive blow came from Coetzee’s right hand, which added to the mystique around it. , Some called the hand “bionic”.

In 1979, The Washington Post quoted a doctor saying that Cootsy’s right hand “could punch a hole in a brick wall.”

Coetzee had a chance to become World Boxing Association champion that year. Instead, John Tate handed Coetzee his first professional loss. In another title fight the following year, Coetzee was knocked out by Mike Weaver.

The match bothered him.

“I could see the punches coming. I could clearly see the crowd when I was down. I could hear the referee counting, but my legs didn’t respond to my brain,” he told The Times in 1981. Told. Don’t fall asleep and replay the scene in your mind’s eye.

Kotzee got the final shot at the title after the Doakes defeated Weaver in 1983. In that fight, he was the aggressor and kept Doakes on the ropes for much of the fight. Supporting Doakes with his left hand, he hit with his right hand, eventually sending him to the mat.

Crucially, Coetzee developed new power with his left hook, which he used to set up his infamous right fist devastating punch.

At the height of his career, Coetzee was one of three people to claim the title of World Heavyweight Champion, along with International Boxing Federation title holder Larry Holmes and World Boxing Council belt holder Pinklon Thomas. was. The division reigned until Mike Tyson became the undisputed boxing champion in 1987.

Coetzee lost the title belt to Greg Page, who knocked him out in 1984. His prime-time career ended in disgrace in 1986 when he was flattened in his first round by the brawny and focused Frank Bruno.

Coetzee married Rina Steyn in 1976. their daughters, Lana and Tana Cozzie; Two brothers, Jhansi and Flip. Sister, Gerda van Aswegen. and seven grandchildren.

Cootsie’s image as a racist icon comes partly from his friendship with his sparring partner, African-American boxer Randy Stevens, and his adoration of Ali. When serving in her army, Coetzee spent most of her monthly salary on copying Ali’s 1975 memoir, “The Greatest.”

In the late 1970s, Coetzee and his wife were invited to his hero’s hotel room. When the TV crew showed up, Ali began taunting Coetzee, shouting that he could beat him “to the moon” and suggesting that Coetzee’s wife was probably a more skilled fighter than Coetzee.

Coetzee, however, preferred to detail what happened when the crew left. “He was also kind,” he recalled to The Times, “and poured us tea.”

[ad_2]

Source link