[ad_1]

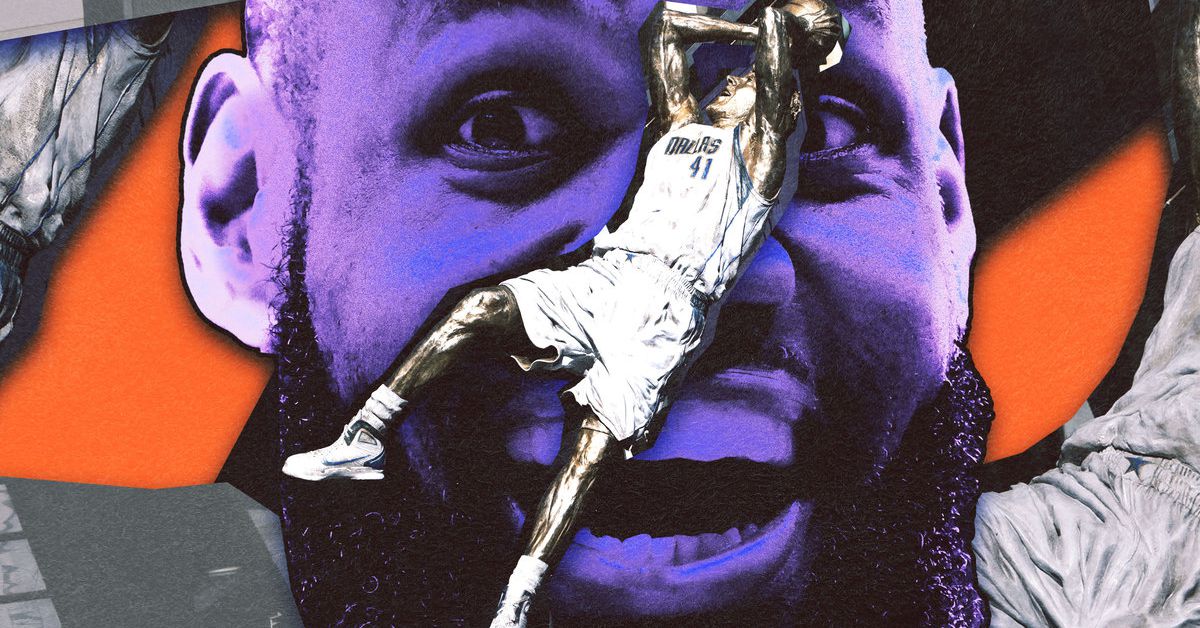

Every statue of an athlete is a contradiction. You can capture a player’s likeness and you can do justice to what they’ve achieved, but it’s impossible to fully render a career spent in motion with a sculpture. The challenge of immortalizing sporting legends is to try anyway—to give a still figure of a runner or pitcher or point guard so many of the markers of movement that it might trick the brain into thinking it’s seeing what it knows to be impossible. To suggest, for example, that the enormous statue of Dirk Nowitzki that now stands outside the American Airlines Center in Dallas could really be leaning back into a jumper, fading away so convincingly that you might even anticipate it landing in a soft backpedal.

“Like it’s a giant feather in the middle of the air, and not 1,500 pounds of bronze,” Omri Amrany, the sculptor behind the statue—and a great many in the NBA world—said by phone recently.

When Amrany—with his wife, Julie Rotblatt Amrany—designed the now-legendary statue of Michael Jordan that soars through the lobby of the United Center, he accentuated the perfect balance of the triangle that was always there in Jordan’s “Jumpman” pose. When he created a monument of Shaquille O’Neal that now dunks on a rim outside Crypto.com Arena, he wanted fans to be drawn in to look up at the statue from underneath it, and yet intimidated by the physical presence of Shaq, weighing a literal ton, hanging over their heads. In capturing Dirk, Amrany pushed the angle of Nowitzki’s signature fadeaway to a point that almost felt impossible.

“When it’s up there in the air, it takes away from the brain the feeling that this is a human being,” Amrany said. “It becomes like a flying object.”

Depending on your angle, you can now see Nowitzki shoot over the top of high-rise apartment buildings, luxury hotels, and the most towering fixtures of the Dallas skyline. These sorts of monuments are a rare gesture—there are only about 16 true, full-body statues of NBA stars in the cities where they played—but Nowitzki had an exceptional career worthy of exceptional recognition. Beyond the revolutionary shooting, the open-and-shut Hall of Fame case, and the title Dirk brought to the city in 2011, he also holds a record that may never be broken: an entire, 21-season career spent with a single NBA team.

“Well,” Nowitzki said after the unveiling ceremony, “we hope Luka can break it.”

Many of the current Mavericks were in attendance when Dirk’s statue was unveiled on Christmas morning, among them 23-year-old megastar Luka Doncic—an all-too-worthy heir of the franchise player mantle. Doncic could be the best basketball player in the world someday, if he isn’t already. Like Dirk, he could be an MVP and a champion, and go down as one of the greatest to ever play the game. And yet the idea of Luka having his own statue at the end of his career seems to run contrary to the working reality of the league he plays in. Many of the NBA’s most decorated active players are already suiting up for their third or fourth teams. Today’s up-and-coming stars are as mobile and as untethered to any one franchise as any generation of players in league history. It’s only going to get more and more difficult to imagine an NBA player becoming a literal, physical part of a city’s architecture—to the point that we could be watching the last wave of statue subjects as we speak.

Every existing NBA monument was built on its own terms, but if we look at the players who have been honored thus far, we can see the criteria behind their selection begin to form:

1. Did the player achieve above and beyond Hall of Fame standards? Think of it this way: The overwhelming majority of the players on the NBA’s 75th Anniversary list—nominally the 75 (err, 76) greatest players in the history of the league—don’t have statues. It’s not enough to be great. The threshold for stonework and metallurgy is so much higher.

2. Is this one of the most significant players in the franchise’s history? Plenty of athletes have statues in their hometown or at their alma mater, but getting a monument outside an NBA arena requires outsized influence on a particular franchise. You simply cannot tell the story of the Mavericks without Dirk, or the Jazz without Karl Malone.

3. Does the player have a lasting and unique connection with the city itself? In almost every case, the NBA players who have had statues built in their honor played at least 12 seasons in the city where the statue was built. The notable exceptions are O’Neal (who played only eight seasons with the Lakers, but won three championships as the most dominant player on one of the best teams ever assembled) and George Mikan (who played only seven seasons in Minneapolis as a Laker and, despite over 30 years of Timberwolves basketball, hasn’t had much competition).

With that general framework, there are a few legends who are all but certain to get statues of their own. Tim Duncan would be a lock if he’s even interested in that sort of recognition—though he could also be honored alongside Gregg Popovich, Tony Parker, and Manu Ginobili at some later date, following Pop’s eventual retirement as head coach of the Spurs. Stephen Curry—one of the few players who could challenge Dirk’s record run with a single team—will be cast in bronze someday. The late Kobe Bryant already has two numbers retired by the Lakers and will inevitably get his own statue in Los Angeles, too. It’s more a matter of when than if for Bryant, and—given the dense mythology around him and the sheer number of iconic moments he was involved in—how exactly his statue might be posed.

“I think the jersey in the mouth—just the grit, the determination to win,” said Hall of Famer Jason Kidd, who played against Bryant in the 2002 NBA Finals and alongside him in the 2008 Olympics. “When you look at the Black Mamba, [it’s] just his ability to help his team or push his team to victory. I always thought the coolest thing is when he puts his jersey in his mouth and he was taking on the world.”

(When asked if he’s had any conversations with the Lakers about a statue for Bryant, Amrany—who was commissioned for the statues of O’Neal, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Magic Johnson, Jerry West, Elgin Baylor, and longtime broadcaster Chick Hearn—declined to comment.)

Bryant, Curry, and Duncan are all tidy cases, where statue-making is concerned—all-time greats who won titles and awards while spending their entire careers with a single team. Then the conversation breaks open, as it so often does, when we consider the legacy of LeBron James. When it was suggested to LeBron in a press conference last month that he would have his own statue someday, he projected humility. “I hope,” he said with a smile. “I hope. I hope.” He will. It would defy every precedent, expectation, and tenet of human logic for there not to be a sculpted tribute to LeBron installed somewhere in greater Cleveland. But it might not stop there; James could be the first player in league history to be honored with a statue from multiple NBA teams, in part due to the undeniable weight of his sprawling career. LeBron already has more All-NBA selections than anyone else. He’s won titles with three different franchises and MVPs with two. In a matter of weeks, he could edge out Abdul-Jabbar as the all-time leading scorer in the history of the league.

“I’ll always say Michael Jordan is the GOAT,” Nowitzki said. “But if [LeBron] really surpasses Kareem in the scoring record, I’m sort of running out of arguments for Michael.”

Would the Heat, a franchise that retired Jordan’s jersey despite him never even playing for the team, really choose not to physically commemorate the best player who actually did? Or would the Lakers, who have built statues for every superstar to lead the franchise to a championship thus far, really pass up the opportunity to recognize James in the same way? These sorts of questions are reckoning as much with LeBron’s accomplishments as they are the state of the NBA. James spent just four seasons with the Heat, and is currently playing his fifth with the Lakers. History says that’s not enough. But for a player who has already changed the league and the sport in so many ways, maybe that precedent is simply the next thing to go.

After all, a more extreme case may already be under consideration. In 2021, Warriors governor Joe Lacob told NBC Sports Bay Area that there was a running list of recent players whom the franchise would honor in some permanent way: Curry, of course; Draymond Green (whom Lacob all but promised a statue after his contract extension in 2019); Splash Brother Klay Thompson; Andre Iguodala, who would be a one-of-a-kind statue candidate in his own right; and mercenary superstar Kevin Durant, who spent just three seasons with the franchise but co-anchored what might be the greatest team the NBA has ever seen.

“I’d say those five guys certainly deserve some sort of ultimate, long-term recognition,” Lacob said two years ago. “And once they retire, I’m sure they will be appropriately honored.”

Durant has openly discussed the possibility of someday having his own statue outside the Chase Center, though he didn’t stay with the franchise long enough to suit up in that arena as a Warrior. The very idea of a Durant statue in San Francisco feels a bit strange—as a choice to honor something so fleeting with something so permanent. And that’s exactly what makes it the perfect test case for statue building in the modern era. Every monument is a reflection of its time. It didn’t really matter that Shaq’s tenure in Los Angeles was the shortest of any NBA legend to get the statue treatment. The 2001 Lakers were one of the best teams of all time because of him. You could say the same of Durant and the 2017 Warriors, and that fact alone creates an avenue for exceptions to be made.

After all, isn’t that what statues are for? Exceptional cases? Even if the standards for what merits a statue shift to reflect the realities of modern player movement, they’ll still be reserved for the kinds of athletes we’ve never seen before. It’s not enough—nor has it ever been—for a player to simply dominate. To be cast in bronze or cut from marble, they have to be part of something genuinely groundbreaking.

As odd as it would be for a statue of Durant to stand for decades where he played for only a few years, it might seem more odd for lesser players to get their own monuments while KD goes without. These sorts of statues always exist in conversation with one another; when a statue of Larry Bird was commissioned for the campus of Indiana State University, the artist specifically designed it to be taller than any statue of Magic Johnson. It takes more than greatness alone to deserve a statue, but how would it sit in the historical context of the game if, say, Kyle Lowry or Damian Lillard were immortalized in physical form, but Durant wasn’t?

Those outcomes are possible, if exceptional in their own way. Players are rarely honored with a statue if they’ve never won an MVP. Even fewer get one without ever winning a championship. The only statued players to never win either are John Stockton and Dominique Wilkins—who overcame that deficit through long, successful tenures with the Jazz and Hawks, respectively. Lillard could end up with a similar body of work, though the fact that he’s effectively had to go out of his way—amid trade rumors and flirtations with superteams—to remain a Blazer for a decade only illustrates how unusual that model has become.

Russell Westbrook could conceivably wind up with a statue in Oklahoma City, in no small part because he stayed when Durant didn’t. Maybe that’s the way it’s supposed to be. Modern superstars can hand-pick their city and their teammates, and become an organizational philosophy unto themselves. They can have everything they’ve ever wanted, but maybe they pay for it in bronze.

There is an inscription at the base of Nowitzki’s statue that reads: “LOYALTY NEVER FADES AWAY.” It’s a tribute to a star who stuck around—21 letters for Nowitzki’s 21 years as a Maverick, in what even the architects behind the statue admit is more of a happy accident than real intention. Mythology tends to work that way. Some of those 21 years were hard on Nowitzki, as he grappled with doubt in his early career, then with persistent frustration, and eventually with his own inevitable decline. Yet as a figure now frozen into the design of downtown Dallas, he represents something else—something that every statue of every NBA great represents in its own way.

“It all boils down to this part of humanity: to get up and keep going,” Amrany said. To endure.

Statues can’t help but smooth over the rougher edges of their subjects, reducing something as fickle as a person to an idea. It’s a timeless sort of myth-making that doesn’t really happen all that much in professional sports anymore. Today’s NBA players are hyper-visible, subject to constant judgment and referendum, and accessible to the point that they’ve been largely demystified. The league is as talented as it’s ever been, and yet it’s harder than ever to frame a contemporary star as a legend. As an icon. At this point, the idea of building something truly lasting in the NBA feels almost impossible.

“This is what makes a statue like that so special: that generations after us will see this after we’re long, long gone,” Nowitzki said. “People are gonna see the statue and Google—or maybe Google is already out by that point. But look it up. Who is this guy? What did this guy do? I think that’s what’s so cool about a statue and sculpture like this. It lives for eternity.”

Duncan, Kobe, and LeBron will live forever in the same way—as will Steph and the Warriors, and maybe Durant, too. If things continue apace, Giannis Antetokounmpo (who in 10 seasons with the Bucks has already won just about everything there is to win) could join them. The next wave of monument candidates beyond them will be different, because the league itself already is. We are living in a revolutionary era of NBA history that has redefined the culture of the sport, from what is expected of an all-time player to the nature of how a fan or a city connects to that player in the first place. If NBA teams are still building statues 20 years from now, those monuments will say something new.

“There’s always something else—something better coming down the line,” Nowitzki said. “So we’ve gotta appreciate that. The game never stops. It keeps evolving.”

[ad_2]

Source link