[ad_1]

Steve Kerr awoke last May 24 with the typical worries of an NBA coach in the midst of the playoffs.

His Warriors held a three-games-to-nothing lead over the Mavericks in the Western Conference finals. A trip back to the Finals was in sight. But Stephen Curry had been pressed into heavy minutes to get there. They’d just lost a key defender to injury. And the Mavericks, powered by the precocious Luka Dončić, were young, feisty and relentless.

The only thing on Kerr’s mind, as he moved through his morning routine, was how to squeeze out one more win. Game 4 was that night, in Dallas.

Then came the phone call. The voice on the other end was trembling, anguished, angry. Kerr had been friends with Mike McBride, an Oakland-based pastor and community activist, for years. He’d never heard him like this.

“He was in tears, and he was just—he just sounded broken,” Kerr recalls.

There had been a mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas, about 350 miles from where the Warriors and Mavericks would play that night. An 18-year-old, armed with a semiautomatic rifle, had entered an elementary school and gunned down several children and teachers.

McBride, the executive director of Live Free USA, had spent years working to curb gun violence. In Kerr, he had found a friend and ally with a potent platform. They’d collaborated frequently on community events around the Bay Area, shared their personal stories and experiences. Kerr had come to know McBride as a strong and passionate leader. Now he sounded gutted.

“It was so heartbreaking to hear him talk about what had happened,” Kerr says. “And I think, like everybody, all I could think of was those poor kids, fourth-grade kids. My God, the terror for them. And then the just, devastation, for the families. It’s just so awful.”

So Kerr made another call, this one to Jessica Gerber—a senior adviser for Brady: United Against Gun Violence—for some advice. What came next was probably the single most powerful moment of Kerr’s four decades in the public spotlight.

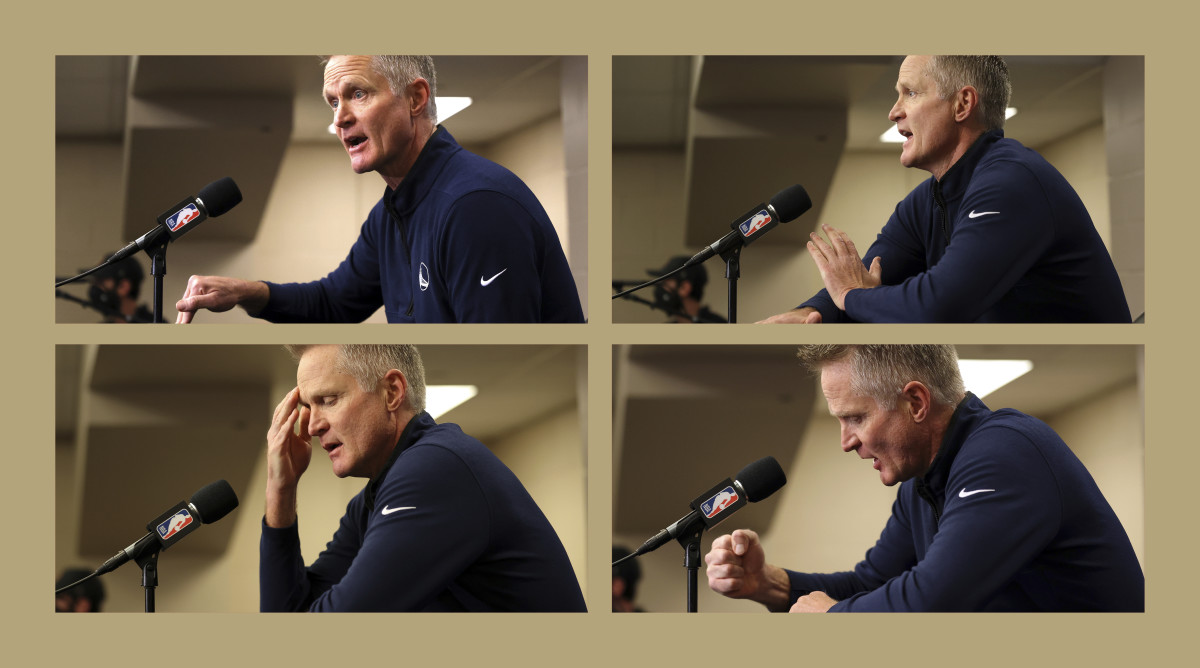

“I’m not going to talk about basketball,” Kerr told the assembled media at his pregame press conference that evening. “Any basketball questions don’t matter. Since we left shootaround, 14 children were killed 400 miles from here, and a teacher. In the last 10 days, we’ve had elderly Black people killed in a supermarket in Buffalo. We’ve had Asian churchgoers killed in Southern California. Now, we have children murdered at school. When are we going to do something! I’m tired; I’m so tired of getting up here and offering condolences to the devastated families that are out there. I’m tired of the moments of silence. Enough!”

For two and a half minutes, Kerr railed and pleaded, his hands shaking, his voice quivering, his eyes watering. He called out the 50 Republican senators who were blocking a vote on background-check legislation. He pounded the table so hard that the microphone with the NBA logo shook. He left without taking questions.

Within minutes, Kerr’s outrage had gone viral across social media and the websites of every major news outlet. The next day, he received phone calls from Vice President Kamala Harris (a Bay Area native and Warriors fan), California Gov. Gavin Newsom and other elected officials, all offering gratitude and support.

Gun violence has long been a personal issue for Kerr, whose father, Malcolm, was assassinated in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1984, when Steve was just an 18-year-old freshman at Arizona. Now 57, Kerr long ago grew comfortable using his platform to champion political causes and social justice. But the Uvalde moment was different—raw, emotional, unplanned, unscripted, bordering on rage. Which is what made it so uniquely impactful.

“Steve Kerr’s speech was so heartfelt and so good that, by itself, it made a difference,” says Sen. Chris Murphy (D, Conn.), a leading advocate for stronger gun laws. “I mean, there were a lot of sports fans that maybe weren’t plugged into the debate on gun violence, who watched that speech and had their minds changed.”

Flash forward to Jan. 17, and Kerr is again speaking passionately on gun violence—only now he’s in a suit and tie, seated at a table in the Map Room at the White House. His audience includes three top advisers to President Biden: Keisha Lance Bottoms, Julie Rodriguez and Stefanie Feldman. The 45-minute discussion also includes Warriors players Klay Thompson and Moses Moody, along with James Cadogan of the NBA’s Social Justice Coalition.

The Warriors were visiting the White House that afternoon for the same reason sports teams usually do: to celebrate their recent championship, trade a few quips with the president and vice president and pose for photos. It’s a tradition that goes back decades and it has nearly always followed the same anodyne script.

But these are different times, and these Warriors—from Kerr to Curry to Draymond Green—are a different team, one that unabashedly broadcasts its political views, on everything from gun violence to presidential politics. Indeed, they eschewed the White House visits altogether after their 2017 and ’18 championships, in a direct rebuke of then President Donald Trump.

The Raptors, who won the NBA title in 2019, also preemptively rejected the possibility of a White House visit. The Bucks, who won the title in July ’21, resumed the custom after Biden and Harris were elected the previous year. (The Lakers didn’t visit the White House following their championship in ’20 due to scheduling conflicts and COVID-19 protocols.)

But the Warriors’ recent visit marks an evolutionary shift—the scripted celebration now doubling as a policy summit. The roundtable on gun violence was conceived by White House staff and pitched to the Warriors, who eagerly accepted the invitation.

When it came time for the formal celebration, in the White House’s ornate East Room, both Biden and Harris praised the Warriors for their activism.

“Look at what this team does,” Biden said, “speaking out against racism, standing up for equality … encouraging people to vote, empowering children and their families to eat healthy, learn and play in safe places, rallying the country against gun violence.”

President Biden praised the Warriors not only for their championship run, but for their activism.

Susan Walsh/AP

Biden thanked Kerr specifically and mentioned the loss of his father to gun violence, a gesture Kerr later called “incredibly flattering.”

“I mean, that’s one you write down and keep in the family history,” Kerr said afterward. “It was a pretty special moment.”

The earlier roundtable was part informational meeting, part lobbying opportunity. White House officials detailed the administration’s efforts, including executive actions aimed at curtailing the proliferation of so-called “ghost guns.” Thompson and Moody discussed the community work they’ve done on gun issues. (Thompson in the Bay Area, Moody in his hometown of Little Rock, Ark.) And they all discussed the role that athletes—and coaches—can play in the political arena.

For Kerr, that calling came later in life. Though his father’s death had shaped his worldview in many ways, it wasn’t until around 2016 that he began to speak out on gun violence and gun policy.

“Anytime we, my family and I, would read a story about somebody dying by gun violence, we knew exactly what the family was feeling, how devastating it was,” Kerr says.

The seemingly constant wave of mass shootings, in schools and grocery stores, churches and movie theaters, became almost unbearable.

“We had had all these moments of silence at games, like five of them in one season,” Kerr says. “It was insane. A moment of silence for the Pulse nightclub, a moment of silence for this, for that, one after another. And it’s like, This is all we can do? Is just have a moment of silence? I mean, it’s the right thing to do. But that’s all? Like, how about doing something? And that’s when I really started to become more active.”

By then, Kerr had become a championship coach, providing a broader pulpit and a greater measure of gravitas than he’d perhaps had during his years as a broadcaster, team executive and player.

“And seeing a lack of action by our government was so disgusting and disheartening,” he says. “I think that’s when I really decided to speak up and say something, and maybe that’s the first time I really felt like I had the platform to do so.”

Meanwhile, NBA players were growing increasingly engaged on the political stage, in part catalyzed by the 2016 election of Trump, whose candidacy was vocally opposed by Curry and LeBron James. Then came the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and the Black Lives Matter movement in ’20. That summer, after another police shooting of a Black man, Jacob Blake, in Kenosha, Wis., NBA players staged a wildcat strike that shut down the league for three days.

Over the past few years, Kerr and Curry have both been unafraid to use their platforms.

Josh Morgan/USA TODAY

One of the outcomes of that strike was the creation of the National Basketball Social Justice Coalition, which now acts on behalf of the league to lobby lawmakers on issues like voting rights and police reform, and to support player activism and political engagement in general.

“We are in different times,” says Cadogan, the executive director of the coalition. “Even the fact that we have the National Basketball Social Justice Coalition is an indicator of the different times, obviously dating back to 2020, where a lot of people were focused on: How do we get engaged as individuals and institutions in the work of social justice?”

The Warriors’ using their White House meeting to discuss gun laws is a logical extension of the movement, and “something that I think we should expect going forward,” Cadogan says. In November, Thunder players visited the White House and engaged administration officials on criminal justice, health and education. “The more of these conversations that NBA leaders get to have, and more broadly, the more that we have exchanges between civil society and our lawmakers and executives, the better,” Cadogan says.

And, says Sen. Murphy, the more that athletes use their platform to advocate for social change, the better. Murphy has been working for stricter gun laws since the Sandy Hook school shooting in December 2012, which happened a month after his election to the Senate. The school is located in the House district he previously represented. It’s taken a decade to build a gun safety movement that can equal the might of the National Rifle Association. But Murphy sees progress—and says speeches like Kerr’s play an important role.

A dedicated Celtics fan, Murphy says he was scrolling through Twitter for NBA news that night when he first saw the video of Kerr. “I knew that it was going to blow up, the minute I heard that first line,” Murphy says.

“I’m not going to talk about basketball.”

“That line was so, so powerful,” Murphy says, “because it was permission for everybody else to stop and recognize the gravity of what we just watched. Because I think in the era of mass shootings, some people don’t know whether they’re supposed to sort of stop and grieve, or whether they’re just supposed to move on, if they happen all the time. And what Kerr was saying is: This is still earthshaking, that this could happen in a school, and it’s so much more important than an NBA game. … It challenges other people to step up and do something in their own lives to meet the moment.”

The legislation Kerr pleaded for last spring—the Bipartisan Background Checks Act, which had been approved by the House—never did win sufficient support in the Senate. But a month after Uvalde, Congress did pass the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, considered the most significant new gun-safety legislation in three decades. Biden signed it into law June 25.

“I think we are at a turning point,” Murphy says. “The passage of that bill is proof that there is now a bipartisan coalition in favor of strengthening our [gun] laws.”

Murphy adds, “I think what the Warriors recognize is that this actually isn’t a very controversial issue. It’s made to look controversial. But actually, 90 percent of Americans think you should have a background check on every gun sale. So sometimes sports figures don’t want to wade into issues that might split their fan base. The issue of guns actually doesn’t split a sports franchise’s fan base, if you’re talking about things like universal background checks. I’ve been so proud of the NBA generally for supporting players’ and coaches’ right to speak up, and I’ve been very specifically proud of Steve and his players.”

Kerr is careful to describe the work as gun safety advocacy, not “gun control,” a term that he says alienates a large swath of the public that might otherwise support common-sense reform. (“Because nobody wants to be ‘controlled,’” he notes.) In addition to background checks, Kerr is supporting a Brady campaign called End Family Fire, which is aimed at requiring gun owners to lock up their firearms in their homes.

“Eight children a day in America are killed by guns, unlocked guns, in the house,” Kerr says. “So you start this program called End Family Fire. Who in their right mind would be opposed to end family fire? It’s not about gun control. It’s not about controlling your life or, you know, taking away your freedom. It’s about protecting your child, and your child’s friends, or the people in your house.”

“This whole issue has to be addressed with everyone in mind,” Kerr adds, “because it’s the only way to take the issue back from all the people in the political world who just use it as an emotional cudgel. Which is so awful, because people are losing their lives every day. And these solutions are out there. … There are solutions where you can get your Second Amendment rights, but we protect people.”

A 45-minute summit tucked into an NBA championship celebration might not, on its own, change the course of U.S. policy. But it was an opportunity to raise public awareness and nudge the movement forward. Kerr, who has won nine titles as a player and coach, had made these White House visits countless times before. None were like this.

It was, also, unfortunately timely. The previous morning, six people had been shot and killed in their home in a small town in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Five days later came a mass shooting in Monterey Park, Calif., leaving 11 dead. And two days after that, another mass shooting in Half Moon Bay, with seven dead.

So Kerr will keep speaking out, keep donating to Brady, March for Our Lives and the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, keep working with Live Free. And despite everything he’s seen—the continued violence, the intransigence of lawmakers and the gun lobby—Kerr says he remains hopeful.

“I believe in the young generation,” he says. “The March for Our Lives kids are so inspiring. And it might take another 30 years to just get the next generation in office, 20 years, to [vote out] all these kooks who are going to support semiautomatic weapons of mass murder over the possibility of losing their political career. Maybe the next generation will be filled with people who actually have a conscience. And I think that’s going to happen.”

[ad_2]

Source link