[ad_1]

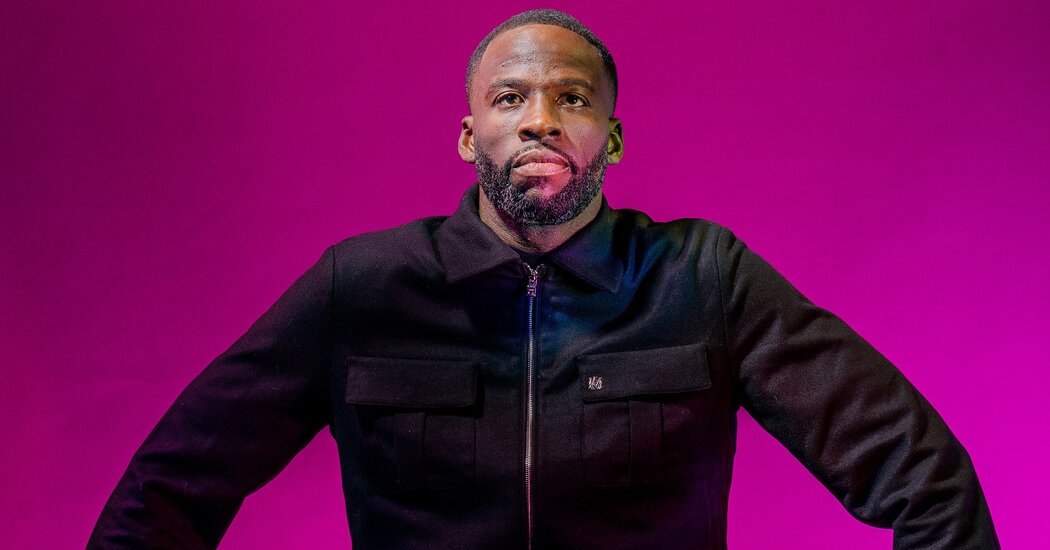

The full story of the N.B.A. over the last decade could not be told without Draymond Green. The raw nerve of the Golden State Warriors dynasty, Green is also one of the league’s most accomplished players. He’s a four-time all-star, four-time N.B.A. All-Defensive First Team selection as well as a former defensive player of the year, and a two-time Olympic gold medal winner. He’s also one of the game’s most compelling personalities, on court and off: equally capable of baffling hotheadedness and coolly cerebral basketball brilliance. This season, though, has so far progressed under something of a cloud for Green, whose assertive play and emotionality have often made him a lightning rod for pundits and opposing teams’ fans. During a preseason practice, Green, who is 32 and who has his own successful podcast, punched his teammate Jordan Poole — an altercation caught on tape. That event presaged what has been a slog of a season for the Warriors, which, this past June, won its fourth championship of Green’s 11-year tenure. At least, that’s how it may look to outsiders. “The average person thinks they understand what they’re watching,” Green says about N.B.A. observers. “They have no idea.”

Because of the way you play and how you can carry yourself on the court, other teams’ fans can really give you the business sometimes. I know athletes always say they ignore booing and stuff like that, but you’re still human; I can’t believe it doesn’t register. So just as a person, what is it like to experience 20,000 people yelling at you? Does it ever make you feel vulnerable out there? In most cases it’s something you grow numb to. Not that it doesn’t bother you, but it’s kind of like, is it supposed to bother me every time? Or do you adjust to your surroundings? For most of us, you adjust. The one time that caught me off guard was Boston in the finals because it was way more nasty than I had ever seen before. I had never openly heard so many racist remarks while on the court. That made it a little different. But as far as heckling, it’s not that it doesn’t bother you, it’s how often are you going to let it bother you?

Have you ever talked with any of the Celtics’ players about what happened last year in Boston? Just because it sounds like the crowd went past partisanship and into something nastier. It seems like that would be an unsettling experience for the Celtics’ guys too, given that the fans who were yelling racist expletives at you were, at least putatively, their supporters. I’ve never spoken to them about that. I don’t think their experience is going to be my experience, so I could kind of care less. Their experience is probably great. Celtics have a die-hard fan base that’s going to root hard for the Celtics. But my experience with their fans was a bit different. Quite frankly, when you’re playing in the N.B.A. finals you’re trying to get any advantage you can to win that game. I didn’t expect any of them to reach out to me or wonder how I was feeling about their environment. If I’m being honest, I’m not reaching out to someone if that were me. But the way I was — the things that were chanted at me were even glorified by our league. I watched people from our league say it’s OK and a part of the game. So, you know, I understood that the important thing was not getting too deep in my feelings about it. I had to go win the championship, and that’s what I did.

Surely no one in the league condoned fans’ yelling racist expletives? Well, they didn’t say it wasn’t OK to say the things that were said to me. It is what it is.

Draymond Green during a game against the Celtics in Boston in 2021.

Jesse D. Garrabrant/NBAE, via Getty Images.

I know that for you having the podcast is a way to share a perspective that the nonplayer media can’t have. But when I’ve listened to it, it’s not as if you’re saying things that are all that far away from what pundits or analysts are saying. So what do you understand and bring to listeners that the media doesn’t? Most of them don’t understand the X’s and O’s. I always tell people — and I’m not saying it from an egregious place; I’m saying it from a logical place — you can’t possibly think you understand basketball as much as me. I study this for numerous hours daily. There are guys that play in the N.B.A. that don’t know the game of basketball, and yet most people think, Oh, I know the game. No, you don’t! And by the way, I’m not saying you have to play or coach in the N.B.A. to know the game of basketball. I’m saying it’s hard to know the game, and very few actually do. No one’s going to value me going on CNBC and breaking down the stock market. No one’s going to look for me to walk into their doctor’s office and say, “Actually, that’s this and not that.” You know why? Because I don’t study that. That’s not my expertise. But still people think they know basketball!

What about when criticism comes from a former player like Shaq, who said the league is soft now, or Charles Barkley, who said you’re not the player you were? Yeah, Charles Barkley went out and said I lost a step. My coach was telling me how I was moving about as good as ever! I work with Charles. Charles doesn’t always watch the games. I don’t take it personal. Went through one ear and out the other. As far as Shaq saying the league is softer, that’s fine. But we didn’t make it softer. The rules made it softer. I would have loved to hand-check somebody if I could. I would love to clothesline somebody and we just get up and walk to the free-throw line and continue playing if I could. We didn’t make those rule changes, nor do we have any say-so. So if Shaq feels that the game is softer, guess what? It is. But I don’t agree that players are softer, and that’s not what he said. He said the game is softer. I agree.

You’ve said elsewhere that growing up in Saginaw, Mich., under not the easiest circumstances, is where your toughness comes from. Your kids are obviously going to grow up in much more comfortable circumstances. Do you ever think about how they’ll develop the toughness that you were forced to develop? Their lives are so different from yours. It’s something I think of daily. Things I want to give to my kids, certain traits, were built in Saginaw, Mich., growing up in the circumstances that we grew up in. My kids aren’t growing up in Saginaw, Mich. Nowhere near it. So how do they get that same toughness, those same lessons, without going through those same things? The reality is they don’t. What I’ve had to understand is that my children will have toughness, because they’ll get it from my wife and me, but it won’t be the same type of toughness that we had. My son DJ doesn’t have to have the same toughness that I had growing up because I needed that to walk to school every day. That’s not his reality. The type of toughness that he needs is totally different. It took me a while to understand that.

How do you? It’s that every day as a parent is another opportunity and obligation to understand your child. You think you’ve got your kid figured out, and then their perspective changes. So it’s daily wanting to better understand my children, no matter how good I may believe that I understand them. Number two, it’s having conversations with fathers that I respect, that are in similar positions, and not being afraid to share your challenges. Because parenthood is not easy. It is not easy at all. But every day you have to make that decision to try to be a great parent. You have to try to figure out what are your best things that you want to give to your kids. And I’m not speaking of materialistic things. I’m speaking of lessons you want to instill.

Green (holding trophy) after helping Saginaw High School win a Michigan state championship in 2007.

Kirthmon F. Dozier/Detroit Free Press/ZUMA Press, via Alamy

What’s the lesson you learned from what happened with Jordan Poole? I think I’ve learned a ton about myself, my temperament, about how to deal with things. I’ve also learned that’s a daily thing, that work that you’re doing in order to better yourself. I’m still not sure that I can say I can 100 percent process the “why,” but what I am certain of is that it’s led me to doing work to better myself. For so long, I stopped doing that work. It’s one thing when you’re not doing something to better yourself and it affects you, but when it starts affecting others, you have to check yourself. You’ve got to put the work in to make sure that you do as much as you can to not do things that negatively impact other people.

I know that when you were a kid, you used to have seizures, and you took medication for them until you were in your late 20s. I can imagine that being a scary thing, and also something that had psychological and emotional ripples or caused you to find ways to compensate for that vulnerability. What’s your sense of how that experience affected the kind of basketball player or person you are? I don’t think it affected who I was, who I am, because my mom never allowed it to. My mom is super strong. My mom never really even explained to me the depth of my seizures until a year ago. Never once until a year ago! She said, “I never wanted you to believe the things that the doctors were saying — ‘you should never drive, never play basketball, never swim’ — I never wanted you to believe that, so I encouraged you to do everything that any other child would do.” Would it have affected me more if I didn’t have the mother that I have? I believe it would have. So I’m thankful for my mother. But how did it affect me as a basketball player? The side effects of the medicine definitely stunted my growth. I was on that medication 20-plus years. My wingspan is 7-1. I’m 6-5-and-¾. I was expected to be somewhere from 6-8 to 6-10. I think a lot about those things.

Just to stick with the Jordan Poole incident: You correct me if I’m wrong, but my reading of what happened is that Poole said something to needle you, probably about money, it set you off and then you reacted the way you did. But you were saying that any specifics are less important than learning why you reacted that way and how to react differently in the future? No, because I’ve been in this league 11 years, and that’s never happened before. So it’s not like, man, I can never let that happen again — as if it’s not a once-in-a-million chance that what happened before will ever happen again anyway! What I’m saying is that in doing personal work, what he said has no bearing. If what he said is the reason that I want to continue to do work on myself, then I’m missing the boat. If you’re just going to blame it on what he said, good luck on the personal work, because that’s deflecting. So when I say what he said is irrelevant, I’m saying that from the standpoint of, Let me not deflect.

Let me ask about this a different way: In the TNT documentary that aired right after the punch happened, you said you were going to have to process the “why” of it. So as best you can, now with the benefit of hindsight, can you explain the why? It’s why the situation ever reached that point, why I reacted the way I reacted. All of those things are part of understanding that why. That’s not something that you just come up with. I think if I could sit here and tell you right now the “why,” it would show you how confused I am. Because those reactions are built over time. You have to learn so much about yourself to get to the bottom of something like that. That takes time.

And how should we understand what happened with Jordan Poole in the context of the team’s culture, which people have pointed to in the past as being uniquely positive or joyful? Our culture is our culture, and there are things within that that we have to figure out. I could go blue in the face trying to get people to understand or not, but I play a team sport, and things about that incident — it still matters to the makeup of our team. Making sure that we can do what we set out to do is more important than wanting someone to know more. Because wanting someone to know more benefits me. Making sure that my team is right and together benefits my team, myself, our families, video coordinators, coaches, equipment managers, marketing staff, our community-relations staff, our public-relations staff. It’s bigger than me. I’d rather work on that than try to get someone to further understand my point of view.

Is the idea of an upbeat, good-vibes winning culture just a fantasy anyway? Because maybe tension is necessary for winning — so many dynasties have had some player who was an emotional wild card. Or maybe the simple truth is that if you’re winning then it’s easy to say culture has something to do with it, but if you’re losing then culture’s not going to help. Winning is hard. Being that it is very hard, it’s impossible that it’s going to feel good all the time. If you’re not having miscommunications, if you’re not having disagreements, that means you’re not doing the things to challenge each other to make each other better, which, in turn, means you are probably not winning. You can be the most joyous person in the world; if you’re losing every game, I don’t think that’s going to produce much joy. It becomes hard to have unity if you’re getting crushed every game.

Green celebrating after the U.S.A. Basketball Men’s National Team won the gold medal game against Serbia at the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

Jesse D. Garrabrant/NBAE, via Getty Images

Insofar as you’re able to separate the objective observer who knows basketball from the subjective participant, is Golden State still a team that can win a championship? That window has to close eventually. The same people that are talking now were talking last year and said we had no chance. And I said then, it still hasn’t been proven when Steph, Klay and myself were together, fully whole, that anyone can stop us. Until someone proves that they can then there’s nothing to make me believe it. There’s no evidence. “Well, you should believe this because of ‘X.’” No. No one has figured it out yet. Yeah, you go through tough parts of the season, and we started the season awful. I mean, even this year the teams that separated themselves —

Like Boston? Yeah, well, we know historically that we probably shouldn’t worry about that because they’ve yet to beat us. That’s how I see it.

Here’s something I’ve always been curious about as a fan: Anybody who makes the N.B.A. is a physical genius. But then you see certain guys who refuse to change their games even though they must be physically capable. I’m thinking of players like Ben Simmons, who has that mental block about shooting, or Russell Westbrook, who’d like to play like the guy he was five years ago. Are those examples of inability to adjust or unwillingness? Is it just stubborn pride? When you’re speaking of players’ ability or inability to adjust, to say pride doesn’t play a role would be a lie. The reality is, to put yourself in the position to where it’s even up to you if you will or can adjust — you’re in that position due to the pride that you have. That pride has led to certain levels of success. You then ask somebody to essentially disregard what has worked for them? To ignore the pride in it would be foolish. Some of it could be inability because what they’re asking you to adjust to, you may not possess that skill anymore because you have not used that skill in so long. So it could be a bit of both. Or it could be you don’t care.

Have you had teammates who didn’t care? I’ve definitely had teammates who I didn’t feel cared. I never view it as someone’s just there for the check, because you have to put a lot of work in to get there. But there are guys in the league that care more about other things as opposed to winning. You run into guys that’ll rather score points than win. Rather get double-doubles than win.

At this stage of your career, how high up is money on the list of factors that you’ll be thinking about when you become eligible to be a free agent after the season? My family, my children: That is a constant that has to be protected and considered at all times. That’s most important. But there are so many different things to take into consideration. Of course money. You have a finite time to make the most money that you can make playing basketball. It’s not like I can do this until I’m 50. Winning is important. Geography — where you’re living, quality of life. I can say these are the things that you’re going to take into account, but those things can change from now to August. Now, saying that, I’ve been here 11 years. It’s not often you have the opportunity to build something special with guys that you enjoy and appreciate, and their skill sets complement each other, and the most important thing for everyone is winning. I don’t take that for granted. You find something great, you ride that as long as you can. But you also don’t know what your options are going to be. So to try to weigh those things and say it has to be X, Y and Z? LeBron James can do that. Kevin Durant. Maybe seven guys in the league can do that. But for everybody else, that’s not a thing. You have to wait and see.

OK, last question: It could be from the pros, college, some pickup game back in Saginaw. What is your absolute favorite memory of playing basketball? The one that gives you the purest, best feeling? 2015. Winning our first championship in Cleveland. Because it was a feeling I had never felt before, and it’s a feeling I’ve never felt again. I don’t know how to describe it. My biggest fear after we won the first championship was that I’d never win again and never be able to experience that feeling again. I was right and wrong. I did win again, but I haven’t experienced that feeling. I never take winning for granted, but it was never the same as that.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations.

David Marchese is a staff writer for the magazine and writes the Talk column. He recently interviewed Lynda Barry about the value of childlike thinking, Father Mike Schmitz about religious belief and Jerrod Carmichael on comedy and honesty.

[ad_2]

Source link